The Protocol System Experience

Angela Walch

Protocol systems are like Rubin’s Vase. When you direct your attention to them, the perspective is unstable, or bistable, to be more precise. Are they a solid thing with a shape and a boundary? Or are they a bunch of component parts that are just temporarily in the same place? In psychology and neuroscience, this undulating perception is called bistable perception1—when you have two perceptions that can emerge from the same sensory input, and your brain swings between the two rather than experiencing them simultaneously.

Figure 1. Rubin’s Vase, the popular optical illusion2

I think of protocols as oughts and of protocol systems as at least two people engaging with a protocol. Another way to say it is that a protocol system emerges when a group of people interacts with a rule.

Protocol systems are always two things at once—individuals and a group. A bistable perception—individual versus system—is actually important in examining them. If we only think about the aggregated whole, we may overlook harms suffered by individuals within the system or problematic power dynamics masked by the continued functioning of the system. On the other hand, if we only focus on individuals within the system, we may miss emergent risks and benefits coming from the system as a whole.

In this essay, based on ongoing research into protocol system experiences, I will take a bistable view of protocol systems and the individuals in them. I’m going to work to humanize the concept of protocols and protocol systems because all of us (except perhaps feral children or true hermits) live our lives inside of many such systems. My overarching goal is to explore how it feels to experience a protocol system as an individual.

Getting to the individual experience requires a description of protocol systems themselves, as part of the world-building necessary for an individual’s experience to make sense.3 If you don’t know what the world in a sci-fi novel is like, you won’t understand why its characters feel depressed when they consume triangles or why they explode when a baby smiles.

Figure 2. A protocol system: the circle represents the protocol and the people interact with it

In laying out the protocol system experience, I’m making a claim that protocol systems exist, that they share common characteristics, and that they are a fundamental part of human life. In a meta sense, I’m telling you about the protocols of protocol systems—what they are, what people do in them, where they go, who they meet, and how it feels to engage with them.

Let’s begin.

A Child is Born

On June 23, 1894, a baby was born to the future King George V and Queen Mary of the House of Windsor in the United Kingdom. Named Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David, at the moment of his birth the baby boy became third in line to the throne, behind his father and grandfather. Upon his christening a few weeks later, baby Edward became a member of the Church of England, which he would inescapably become the head of upon his ascension to the crown.

Edward’s life was full of privilege and great wealth. He became a fashion icon all over the world, had relationships with the most eligible bachelorettes of the 1920s and 30s, and raised a lot of hell. This activity was frowned upon by his family and the government, but things really came to a head when Edward fell in love with soon-to-be-divorced Wallis Simpson. When Edward’s father died in January 1936, Edward became, as expected, King Edward VIII and the titular head of the Church of England. Alas, the Church could not allow its figurehead to flout its tenet of opposing remarriage after divorce, so Edward was faced with a choice: marry the woman he loved once her divorce was final or perform his role as king and titular head of the Church. Edward could not choose both paths and in December of that year and to the shock of the world, he abdicated both his role as king of England and his role as head of the Church of England so that he could marry Wallis Simpson. Though he was able to retain wealth and many privileges of royalty, his family relationships and his life were irrevocably and dramatically altered through his choice of bride.4

Clearly, King Edward VIII is an edge case—not too many of us are members of a royal family and have our fate so publicly determined at birth or have to give up so much to alter our destiny. After all, there have only been 63 monarchs of England and Britain during the last 1,200 or so years.5 But I’m not so sure that Edward VIII is that different from the rest of us. He was auto-enrolled into several key protocol systems upon his birth, experienced the inherited roles as a bad fit with who he was, and ultimately exited his predestined role (king), severely damaging his position in his family of origin, the United Kingdom, and the Church of England. The kingship, religious, and family protocol systems tightly interlocked, so for Edward, rejecting one to enter a marriage protocol system with Wallis Simpson meant rejecting them all.

Defining Protocols

When I talk about protocols, I mean rules created by humans6 that shape the behavior7 of groups of people. Protocols can be explicit or implicit and they go by plenty of other names: norms, laws, standards, customs, traditions, taboos, contracts, commands, regulations, manners, morals, values, expectations, et cetera.8 Protocols tell us the shoulds, oughts, and have-to’s and my view of them closely resembles the anthropological concept of culture. If culture is the set of activities and values a group of people shares, then that culture, like a protocol, provides signals to members of the group that they should behave in particular, normatively preferred ways (i.e., performing that set of activities; proclaiming and living those values).

The purpose of a rule or an “ought” is to guide the behavior of an individual—to point out which path to take. When individuals stray from the path, they put something at risk: their freedom, their resources, their relationships, their status, sometimes even their life. If I drive my car on the sidewalk, I risk losing my driver’s license, destroying property that I will have to pay for, and injuring people to whom I will be accountable. If I come out as an LGBTQ+ person, I risk being shunned by family, friends, or colleagues, and, depending on where in the world I live, potentially my life. If I commit a crime as president of the United States, I risk . . . well, never mind. But generally, there are rules of behavior in protocol systems whose purpose is to constrain personal choice, ideally for some larger purpose, as Janna Tay reminds us in “A Phenomenology of Protocols.”9

The E=mc2 of Protocol Systems

A protocol system is made up of a protocol, at least two people, and those people taking actions in relation to the protocol.10 In (unnecessary) equation form, it looks like:

Protocol system = A + B + C

A = a protocol

B = more than 1 person

C = actions by those persons in relation to the protocol

This definition only provides the components of a protocol system; it doesn’t tell us how successful a system will be, how willing people will be to participate, how long it will endure, or whether its outputs will be desirable (however defined). You can evaluate protocol systems normatively, as Nadia Asparouhova does in “Dangerous Protocols,”11 but here I’m trying to be purely descriptive.

Under my definition, the category of protocol systems contains pretty much all group activities.12 I see protocol systems as the biggest bucket of human systems, incorporating social institutions, sociotechnical systems, and human organizations of all types and sizes. To name some examples, protocol systems include nations, religions, schools, political parties, languages, professions, families, gangs, cults, blockchains, and countless others. That means we are each enrolled in countless protocol systems during our lifetimes.

Sharp-eyed readers will notice that I deliberately excluded several seemingly important ingredients from my definition of a protocol system:

- belief by participants in the ideas and values embedded in the protocol system

- consent by participants to be governed by the protocol system

- allegiance by participants to the protocol system

- desire by participants to achieve a common goal

- awareness of the protocol system by participants

- knowledge or understanding of the protocol system by participants.

These features may be present in many protocol systems, but don’t have to be. If these elements were required, I’m not sure there would be anything left in the protocol system category.

For instance, it is estimated that only one percent of Catholics agree with the church’s teachings on abortion, capital punishment, and euthanasia.13 A child who is born into citizenship in a particular nation has not affirmatively consented to that nation’s governance.14 Members of professions may not feel a sense of allegiance to their profession even if they practice it (hello, lawyers15). Participants in an education system (teachers, administrators, students, parents, school boards, the community) may have different goals from one another (getting paid, producing high test scores, learning, social engagement, and more). And plenty of us drift along a path that we haven’t consciously chosen,16 repeating our parents’ parenting techniques,17 going to the best college possible, or wearing Lululemon everything in middle school.18

What You Do: Roles and Protocol Actions

Given my broad definitions of protocols and protocol systems and my claim that humans spend our lives in them, just what is it that people are doing in and around these systems?

Two things: performing a role and taking protocol actions.

Roles

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts.19

A role is the part a person plays in a protocol system.20 Your role is how you are known to others and it has a name that distinguishes it from other roles within the system. In a family, you may have a parent or child role. In a religion, a minister or a parishioner. In a nation, a president or a citizen. In a blockchain system, a developer, validator, or token holder. Given that we each participate in many protocol systems, each of us “in [our] time plays many parts,” some simultaneously and some sequentially.

For each role in a given protocol system, there are expectations—protocols—for how a person in that role should behave, what path they should follow, and how they should relate to others inside and outside the system.21 These protocols may be explicit or implicit. For the role of junior faculty at a university, for example, there are generally written and unwritten rules about what is required to achieve tenure, how to interact with senior faculty, how many university events to attend, what to wear, how much to self-promote, and more. Performing a protocol role successfully yields certain rewards (tenure!), while an unsuccessful performance has negative consequences, potentially including being cast out of the protocol system or even death.22

The role you play within a protocol system has major consequences for your life experience. If you have a role with little power in a protocol system (say, a woman in a patriarchal system), your choices, resources, opportunities, and experiences are very different than if you had a powerful role in the system (say, a man in a patriarchal system).

Sometimes people have the ability to pursue preferences about what role to play in a protocol system (“I want to be vice president of the student council”); in other cases they do not, such as when they are autoenrolled in roles in protocol systems at birth or during childhood (e.g., when parents assign a default heterosexual role to their young child). Sometimes people believe they are autonomously choosing to join a protocol system and take on a certain role, but don’t realize they are taking this action because their role in a different protocol system requires it, an effect of what I call protocol determinism (e.g., you become a doctor because your role as a daughter in a family protocol system compels you to abide by your parents’ wishes).

We may struggle to see that we are performing a role when we lack awareness of or insight into the relevant protocol system. A role can be mistaken for “who you are” or “your identity,”23 implying that it is a fundamentally unchanging aspect of the self when instead a role is subject to change, rejection, or readoption once a person gains awareness or insight. This essay does not develop a full theory of what “the self” constitutes as that is a larger endeavor, but it does acknowledge the felt difference between the internal self and the self presented to the world.

If there is a bad fit between your internal self and your role, you can suffer from a sense of compelled inauthenticity, or dysphoria, while if there is a good fit, and you authentically align with your role, you can thrive. Here, I am borrowing the concept of dysphoria from gender dysphoria, in which there is “a marked incongruence between one’s experienced/expressed gender and their assigned gender” along with “clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.” I think this sense of incongruence (bad fit), distress (dysphoria), and impairment is present not only when there is a mismatch in gender experience and assigned gender, but when there is a mismatch (or bad fit) in any protocol system (whether of the role or the protocol system itself to the person). You can suffer a poor fit and dysphoria in a protocol system whether it is a career, religion, or any other kind. If the role or protocol system feels inalterable, the suffering from dysphoria can be intense, affecting all facets of your life.

Protocol Actions

In addition to performing their roles, people in and around protocol systems perform certain actions that are common across all types of protocol systems. I call these protocol actions.

A protocol action is an action performed in relation to a protocol system that either sustains or weakens that system.

- Supportive protocol actions serve to support, grow, or extend the life of a protocol system.

- Destructive protocol actions serve to weaken, shrink, or kill off24 a protocol system.

- Double-edged protocol actions occupy a middle ground and can be either supportive or destructive depending on the context. Some may help a system grow rapidly but contribute to an early death, while others may foster slow or little growth, but help the system live a long life. These actions are double-edged because when you take them, you are taking a risk on whether they will ultimately help the system or hurt it.

Figure 3

Figure 3 depicts a long list of protocol actions according to whether they are supportive, destructive, or double-edged. A few examples of supportive protocol actions are recruiting new people to join the system, creating loyalty amongst participants, and maintaining the system. Destructive protocol actions include not following the protocols of the system, encouraging participants to leave the system, and publicly criticizing the system. Finally, double-edged protocol actions include actions that could help or hurt the system, depending on the context, such as educating participants and would-be participants of the actual (rather than mythologized) pros and cons of the system, preventing participants from leaving the system, or enrolling new participants through coercion or deception. Forced participation in a system may allow it to grow for a period of time, but if the constraints become too tight, participants ultimately revolt.

Life and Death Protocol actions are analogous to actions we perform individually to preserve or shorten our own human lives. Supportive life actions would include eating nutritious foods, getting plenty of sleep, and exercising, while destructive life actions would include eating unhealthy food, not getting enough sleep, smoking cigarettes, and not exercising. Double-edged life actions might include working a stressful and demanding but personally meaningful job, losing or gaining a great deal of weight for a movie role, or bearing a child. If not enough supportive life actions are performed, and too many destructive life actions are, death is hastened for the person (as a general rule, though there are certainly exceptions).

If you think about what is necessary to sustain a human life, for instance, you will learn about the need for food, water, air, and protection from the elements, which work to keep the systems of the body operating—the heart beating, the blood pumping, the nervous system sending signals, the filtering systems processing waste, the immune system fighting off invaders, and the digestive system reaping energy from what the body consumes.

If people keep performing supportive protocol actions towards a protocol system, they can keep it alive. If a tipping point occurs where too many people are performing destructive protocol actions, the system heads toward death.

Ultimately, I think a protocol system dies when people stop performing supportive protocol actions in relation to it. This explains why protocol systems must keep taking in new participants to perform supportive protocol actions. For some protocol systems, that may involve having more children who are auto-enrolled in the protocol system (see the “Quiverfull” theory discussed in the Shiny Happy People docuseries on the Duggar family and their religion25). For others, it may involve taking over other protocol systems or even trying to keep the protocol system alive after early participants have died, through family traditions, practices like primogeniture,26 giving alumni offspring preferences in college admissions, or creating political dynasties like the Kennedys and Bushes.

Many more supportive protocol actions than destructive protocol actions exist, at least by my reckoning, suggesting that protocol systems require lots of tending to form and endure, and that they are vulnerable to a smaller but potent set of destructive protocol functions. However, the long lives of protocol systems such as the Catholic Church or the institution of marriage indicate that certain types of protocol systems can be resilient over centuries.

Good and Bad People perform supportive and destructive protocol actions in both good and bad protocol systems, if we are rating a protocol system on its moral worth. Just as performing supportive life actions (eating healthy and exercising) can keep a morally flawed person thriving physically, so can supportive protocol actions keep a morally reprehensible protocol system (e.g., slavery) going. Similarly, a morally good person (however defined) can be brought down by destructive life actions (poor diet, isolation, sedentarism) just as a morally good protocol system (e.g., providing healthcare to people) can be destroyed by destructive protocol actions (e.g., exploiting money-making opportunities in the system’s design). Bad protocol systems can live a long time and good ones can die young.

The outcomes that double-edged protocol actions generate seem more aligned with the values/purposes of the protocol system. If truth, openness, and ongoing assessment are values of the system (i.e., are embedded in its protocols), then performing double-edged protocol actions (like truth telling or pointing out issues) may strengthen the system by enabling change (think upward reviews in companies). If truth, openness, and ongoing assessment are not values of the system (perhaps because the protocols bake in power differentials that certain participants benefit from), then performing double-edged protocol actions may keep the system alive for a long time, but may ultimately sign its death warrant when conditions for the less privileged in a protocol system become unendurable.

Who You Meet: Protocol Archetypes

The Protocol System Experience is filled with common personas, or protocol archetypes, who appear in all types of protocol systems, from nations to middle school popularity systems. As a person undergoes their Protocol System Experience, they will encounter (or act as) various protocol archetypes. A single person may act as multiple protocol archetypes in a single protocol system.

Protocol archetypes are a variation on psychiatrist Carl Jung’s archetypes,27 which Jung describes as common figures that humans all have in our collective unconscious. Joseph Campbell builds on Jung’s Archetypes in his vision of the hero’s journey,28 in his description of the various common characters who appear along the journey. Protocol archetypes may overlap with Jung’s and Campbell’s visions.

Some protocol archetypes are defined by the protocol actions they perform (which may support or undermine the system), while others are defined by their place in the power structure of a protocol system, or by their awareness of or insight into the protocol system. A given protocol system may not include all of the protocol archetypes, but it will include at least some of them.

While defining archetypes is a subjective exercise, a set of archetypes is described in detail in the appended table. In this scheme, protocols can be described by archetypes categorized into guardians, threats, dualists, hierarchics, and consciousians.

Guardians First, we have the performers of supportive protocol actions. As a cluster, they serve as the guardians of the protocol system—helping it to grow and endure.

Threats Protocol archetypes can perform destructive protocol actions, acting to weaken or destroy a protocol system. We can call them threats.

Dualists Protocol archetypes can perform double-edged protocol actions—the dualists. In some circumstances, the dualists strengthen a protocol system; in others they act as threats.

Hierarchics Protocol archetypes can be defined by their place in the power structure of the protocol system—the hierarchics.

Consciousians Finally, we have protocol archetypes defined by their awareness of and insight into the protocol system (their consciousness of it)—the consciousians.

The archetypes are not mutually exclusive—people will often play more than one role.

Where You Go: A Protocol System Journey

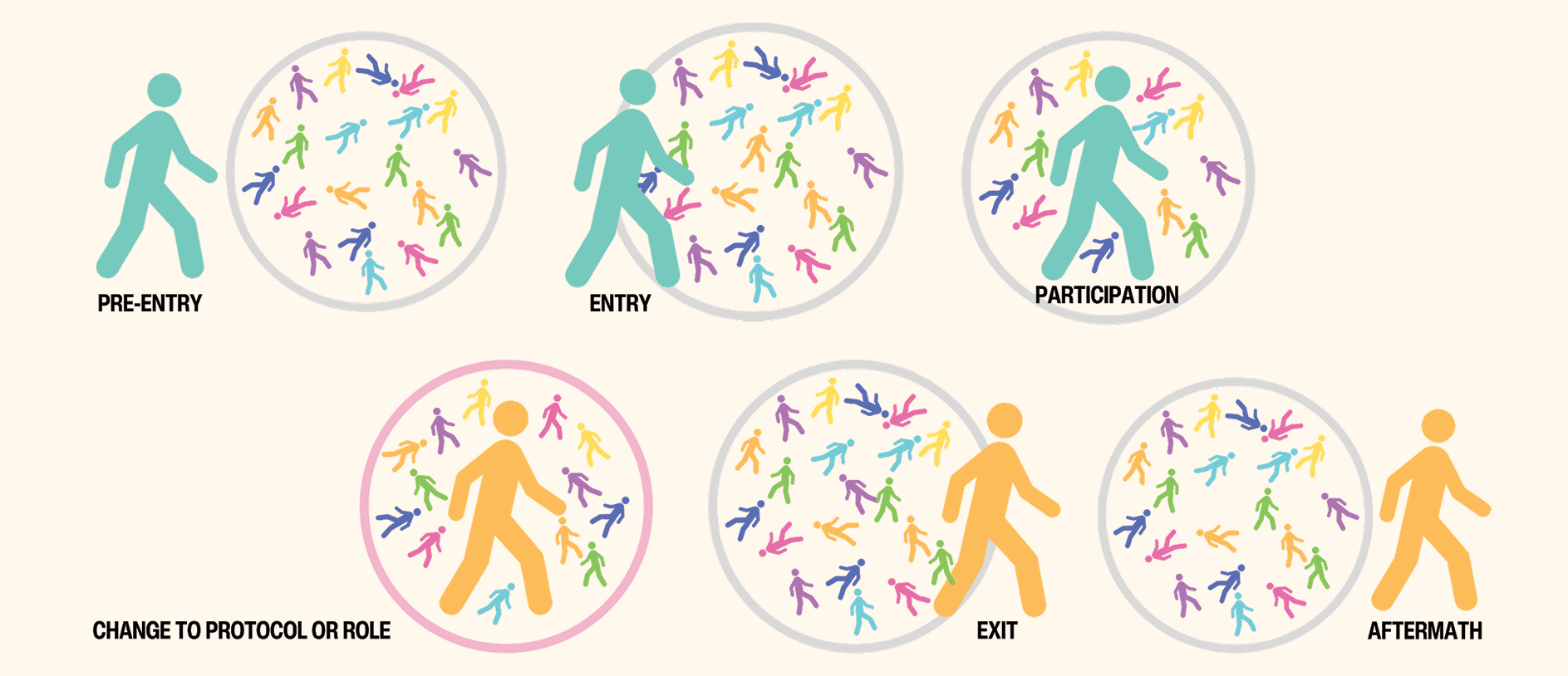

Figure 4. Here’s Pip participating in a protocol system along with other people. Pip and the other people are surrounded by a protocol that changes their direction whenever they bump up against it like fish in an aquarium.

I’d like you to meet Pip, our “Person in Protocol,” who spends their life inhabiting and journeying through countless protocol systems. As you may remember from Lord of the Rings, “Pippin” or “Pip” is short for “Peregrine,” so Pip is a real traveler. We are going to plot the stages of a generic journey through a protocol system with Pip as our wayfarer.

Figure 5

Figure 5 shows Pip in various stages of moving into and out of protocol systems over the course of their life. As you can see, Pip goes through a set of inflection points, or stages, that are common to all of the protocol systems in their life, whether the protocol system is a blockchain, a religion, a career, a friendship, a marriage, or a nation. Stages like preparing for entry, the moment of entry, participating in the protocol system, changing the protocol system, exiting the protocol system, heading off to something new, or returning to the protocol system.29 Pip may not do all of these in every single one of their protocol systems (maybe Pip gets married and stays that way until death, so never exits their marriage protocol system, or maybe Pip never goes through pre-entry into a religious protocol system because their parents enroll them in it at birth), and they may not always be done in the same order, but this is the flow for Pip.

Pre-Entry When Pip is preparing for entry, they may investigate what they need to do to gain entry, then educate or otherwise prepare themselves for entry, and finally complete the qualifying requirements. Pre-entry involves things like completing education or training requirements, licensing exams, applications, interviews; making promises to behave a certain way (e.g., taking an oath); paying money or other resources; wearing certain attire; grooming a certain way; living in a certain place; speaking a certain way; or participating in hazing rituals like drinking, humiliation, or committing a crime. Sticking with Pip’s marriage protocol system, they may have to get to know the person they want to marry, buy a ring, propose, get a marriage license, and plan a wedding in the pre-entry stage.30 For a legal career, pre-entry may involve learning what lawyers do,31 applying to law school, attending and graduating from law school, passing the bar exam, and finding work as an attorney.

Entry Entry into a protocol system is the fleeting moment when Pip crosses the threshold of a protocol system on their way into it. They move from an outsider to an insider as Pip transforms into a participant and assumes their role in the system. In this phase, they are making (or someone else is making on their behalf) a “choice to enter.” Examples would be matriculating at a university, completing a marriage ceremony, signing a contract, being baptized into a church, or being born into citizenship.

Participation Once inside the system, Pip begins to perform their role (whether assigned or chosen). The role Pip has is distinguished from other roles within the system and it is how they are known to others. In a family protocol system, for instance, Pip may have a parent or child role. In a religion, a minister or a follower. In a blockchain system, a developer, validator, or token holder. For a given role, there are protocols for behavior, how to interact with participants and outsiders, and what path to follow. In addition to their role, Pip may also perform protocol actions and serve as one or more protocol archetypes.

Change to Protocol or Role In this stage, Pip works to change either their own role in the protocol system or the protocol itself, or both. This could be as simple as changing from an alto part to a soprano part in a choir protocol system, or as momentous as moving from a female role to a non-binary role in a gender protocol system. As to changing the protocol itself, this could be something relatively minor like no longer requiring yearly vehicle inspections as part of a transportation safety protocol system, or as fundamental as opening the vote in national elections to women for the first time. Change in a role may be driven by feelings of a poor fit with the role and to escape the resulting dysphoria, while change in a protocol itself may be driven by a larger scale mismatch/dysphoria for a group of people or desires for technical or efficiency improvements.

Exit Like the entry stage, the exit stage is a moment of transition, only this time Pip leaves the system instead of joining it. They are saying goodbye to their role and potentially relationships, resources, or status as they go. Depending on the centrality of the protocol system to Pip’s life, this could be devastating, like divorcing or being divorced by a spouse, or even being excommunicated by a religion. In other contexts it could be freeing and exhilarating, like graduating from the high school protocol system to begin an adult life.

Aftermath The aftermath occurs after Pip has exited their protocol system. They are no longer bound by the protocols of their former system, but they may be adrift and unsure of where to go next. Pip might join another protocol system (like a different church, or immigrate to another country), or they might build their own protocol system and persuade others to join, perhaps a new religion or a new blockchain system. Pip may also attempt to re-enter their former protocol system or just wander aimlessly for a while. Pip may also have protocol scars or, if lucky, some protocol afterglow, as I discuss below.

Opportunities for Agency

The various stages of Pip’s journey that I’ve laid out sound relatively peaceful and linear. Pip learns of a protocol system they might like to join (hmm, college!), does what’s necessary to join it (get admitted), participates by fulfilling course requirements and having the full college experience, and then is ready to graduate (exit) to go on to a new protocol system (work!), and Pip begins the cycle again. Would that it were that easy for Pip.

At each of the inflection points along Pip’s journey, they must make a decision about what to do next—whether to join a protocol system, whether to keep performing their role and other protocol actions to keep the system going, whether to try to change their role or the protocol itself, or whether to leave or just live with the status quo. Each of these inflection points confronts Pip with a moment of agency, where they must decide whether to stay on the protocol’s path, or to make a decision on their own.

I should say, rather, that the inflection points are opportunities for agency that may be exercised by Pip themself or by others on behalf of Pip. Particularly during Pip’s infancy and childhood, others (like parents, teachers, and government officials) make decisions for Pip or influence or even compel Pip to make a decision different than one Pip might make on their own (e.g., like enrolling Pip in a particular school (or not), choosing a religion (or not) for Pip, or choosing where Pip lives and is a citizen).

I’m not sure that it’s even possible for Pip to make an autonomous decision when faced with opportunities for agency. It seems very difficult, if not impossible, as so many things can get in the way:

Lack of Awareness Pip may not even be aware that they are engaging with (or participating in) a protocol system. If they can’t see the protocol system, they may not even see that they have an option when they encounter an opportunity for agency. The protocol will always provide the answer.

Lack of Insight Even if Pip is aware they are engaging with a protocol system, they may lack insight into or deep knowledge about the protocol system, leaving them unable to truly assess the pros and cons of their decision.

Protocol Overhang Pip may be controlled by what I call “protocol overhang,” and be unable or unwilling to acknowledge it and disentangle themselves from it.

Interactions Pip is surrounded by people, inside and outside the protocol system, and Pip’s interactions with these people impact Pip’s choice at moments of truth. It may simply be too difficult for Pip to make an alternative choice.

Let’s flesh out of each of these barriers to autonomous decision-making a bit more.

Lack of Awareness

It sounds kind of crazy, but Pip can participate in a protocol system without even being aware that they are doing so. They can play their role, perform protocol actions like recruiting others into the protocol system or defending it from critique, and auto-enroll their own children in the protocol system, all without awareness that they are responding to the protocols of the system, and not necessarily their own wants or desires. This, despite the fact that Pip, though imaginary, is not a robot and is not asleep or physically unconscious.

The young fish in David Foster Wallace’s famous 2005 Kenyon College commencement speech show a lack of awareness of their own protocol system. Wallace describes a scene of two young fish swimming together through the ocean. An older fish swims by them and asks, “Hey, how’s the water?” The young fish keep swimming, and one turns to the other and asks, “What the hell is water?”32

If Pip has awareness of a protocol system, they are “seeing the water” that they swim in—the culture and world (protocol system) that surrounds them, shapes them, and constrains them. When aware, Pip sees the ocean they swim in, knows that other oceans and non-oceans exist, knows how they got into their ocean, and understands that the ocean currents affect their movements.

Awareness allows Pip to be an observer of themselves and the protocol system along with participating in it. For example, as a parent it’s easy to repeat the child rearing (or other33) practices you were raised with without even realizing it. If your parents disciplined you with spanking or grounding, you may automatically reach for those tools yourself, without realizing that you are participating in a parenting protocol system with unarticulated but very real rules.34 Without awareness, you may never examine whether you agree with these disciplinary protocols, and, through your behavior, may unwittingly pass along those same practices (and protocols) to your own children.

Pip has awareness with regard to a particular protocol system if they know:

- that they are entering, participating in, or exiting it;

- that they play a certain role within it;

- that there are alternatives to joining or participating in this particular protocol system;

- whether they entered the system by choice or under the influence or control of others; and

- that the protocol is influencing their thoughts and actions.

If Pip was enrolled in a protocol system as a baby or young child (without the ability to make their own choice), they are more likely to lack awareness of the protocol system, and to see their protocol system as “just the way the world is” and their role in the protocol system as “who I am.”

Lack of Insight

Insight is about the depth of knowledge and understanding Pip has about a protocol system.35 Insight allows a person to make a meaningful choice about their participation and role within a protocol system. Without insight, Pip cannot make a useful evaluation of the personal costs and benefits of their participation in the protocol system, the effect of the protocol system on others, or the moral worth of the protocol system or their participation in it. Participation without insight is a superficial, childlike way of engaging with a protocol system.

Pip has insight if they understand:

- how a protocol system is structured;

- the various roles people play in the system;

- how power works within the system; and

- the effects (positive and negative) the protocol system has on people inside and outside of the system.

Protocol Overhang

Protocol overhang happens when a protocol system’s control reaches beyond (or overhangs) its active participants. You can picture protocol overhang as tentacles extending outside the boundaries of a protocol system to steer people outside of it or to bind other protocol systems to it (or consume them). I see there being four types of protocol overhang.

Protocol Overlap. Protocol overlap happens when two or more protocol systems are linked together for a person, and participating in one of the systems requires participating in all of the systems (and the same for exiting the systems). Like a prix-fixe menu, your choice regarding one linked protocol system applies to all of them, whether you want it to or not. For example, imagine that in your family, most everyone is a member of a certain religion, and there is the assumption that all children in the family will be members of the religion, and their children will also be, ad infinitum. Choosing to leave one protocol system (the religion) could disrupt your participation in the family protocol system, potentially even resulting in you being cast out of the family. You could also imagine your career protocol system being linked to your family protocol system: If you don’t go to medical school, or fill your role as a member of the British Royal Family, or take over the business your parent started, then you may lose your role or even your participation in the family protocol system (as has largely happened to Prince Harry36 and did to King Edward VIII37 before him).

Protocol Determinism. Protocol determinism is closely related to protocol overlap, but is worth distinguishing. Protocol determinism occurs when Pip’s choice to enter a protocol system or take a particular role in it is dictated by their role in a separate protocol system. For instance, imagine a woman gets married and has a child before pursuing a career. Later, she regrets those choices, as she is not happy in her roles as wife and mother, and has limited career opportunities. In reflecting on her choices, she realizes that she never considered whether she actually wanted to marry or have a child or whether those roles would be a good fit for her. She now sees that she entered the marriage and motherhood protocol systems because that was expected as part of her role as a daughter in her family-of-origin protocol system. Her decisions regarding marriage and children were not made with autonomy, but through protocol determinism, which works to invalidate autonomy in downstream protocol systems.

Protocol Outreach/Conquest. Protocol outreach occurs when a member of a protocol system attempts to persuade an outsider to join their protocol system. Protocol conquest is persuasion, as Carl von Clausewitz would say, “by other means.”38 I.e., conquest is forcing someone to join a protocol system, or even one protocol system subsuming or taking over another one (think hostile takeovers of companies or the colonization of the Americas). Protocol outreach could look like missionaries trying to persuade someone to join their church, members of a multi-level marketing scheme recruiting new sellers, or prestige law firms wooing summer associates to work for them. Protocol outreach functions as a tentacle reaching out from a protocol system to take in new participants or to reabsorb former participants– think The Blob39 enveloping everything it touches—and may involve incentives to enter the system.

Protocol Scars. Protocol scars are ongoing injuries or damage (physical, mental, or emotional) that endure after you leave a protocol system. You may have protocol scars from your involvement in a marriage protocol system, for example, if the dynamics of the system were abusive. Even after leaving the marriage, you may have trauma that impacts your health, a negative self-image that makes you hesitant to enter another relationship, or a dire financial situation. People who were raised in “Purity Culture” as part of their religious upbringing report long-lasting trauma that permanently affects their sex life.40 Protocol scars can limit autonomy going forward unless they are addressed (for instance, by therapy or other efforts at recovery).

Protocol Afterglow. Protocol afterglow is positive traits, memories, or goods that stay with you after you leave a protocol system. You might experience protocol afterglow after leaving one career protocol system (e.g., a public school teacher) to enter another (running your own restaurant). You may take your planning skills, ability to stay calm under pressure, and relationships with the community into your new career. Unlike protocol scars, protocol afterglow can be good for your autonomy (although, if you move from a big fish/small pond protocol system to one in which you are a small fish in a big pond, your protocol afterglow may taint your decisions in your new setting).

Interactions

So far, we have been focusing on Pip navigating the Protocol System Experience, primarily from an internally-focused perspective. However, a protocol system is a group of people doing things in relation to protocols. By definition, then, the Protocol System Experience is characterized by interactions with other people. These interactions can either increase or decrease Pip’s autonomy.

Exercising autonomy in a protocol system is not as simple as raising your levels of awareness or insight. Even if Pip is at the highest level of both, they may still feel unable or be physically unable to make a change to their situation. One reason behind Pip’s inability to act on their desires is their interactions with fellow participants in the protocol system. The actions and inactions of others may cause Pip to act differently than they wish. The protocols of protocol systems come with a signal of desirable behavior and a consequence for not engaging in it. Other humans, through Pip’s interactions with them, impose these consequences on Pip, whether the consequence is loss of resources, health, relationships, or status. Fear of the consequences is often enough to make a person alter their behavior. For instance, a person with gender dysphoria may not reveal themselves in order to avoid acts of hate or rejection, or a leader’s aide may not reveal a leader’s mental incapacity so they don’t lose their job.

———

This completes our whirlwind tour of protocol systems. In this essay, I have tried to provide an alternative lens through which to view group activity. Sometimes, just reframing the way we look at a common practice opens up new questions and insights and enables different decisions. I think this framing of protocol systems has resonance both for self-reflection and for system-level analysis, as it asks us to consider the effects of protocol systems on the individuals within them. Protocol designers, envisioning the often utopian objectives their systems can (in theory) achieve, would do well to maintain a bistable view of them, drawing from both the system level and the individual perspective in their efforts. I’m yet to be convinced that a utopian human system can exist, but I know it can’t without accounting for the individual experience. Δ

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful to the entire Summer of Protocols group for inspiring me to think creatively and to put a structure to ideas I’ve been mulling over for many years. Special thanks to Tim Beiko, Venkatesh Rao, and Josh Davis for stimulating the team of researchers and providing scaffolding to make the study of protocols a “thing.” Thanks to Mashal Waqar, Jinzhou Wu, Alice Noujaim, Janna Tay, Kara Kittel, Toby Shorin, Shuya Gong, and Seth Killian for invigorating brainstorming and idea-testing sessions and to all the researchers for making me see the world in new ways. Thank you to the Ethereum Foundation for funding my work. Most of all, thank you to my husband, daughters, family, and friends who supported me in this project and in my larger project of self-renovation.

It has been challenging to write a different type of paper than I’ve previously had to write in law and academia. As opposed to a bullet-proof, citation-heavy article, this has been more of a “noticing” kind of essay, where I’ve tied together a bunch of things that I’ve noticed, learned, and thought about, and described the sense I’ve made of them. The claims in this series of essays are not provable or proven in a scientific sense, but I offer them up for use, improvement, and critique (and hopefully to make you think deeply about your own life and protocol systems).

Explorations of the Protocol System Experience are both intellectual and personal for me. Theorizing about the human experience can’t help but be.41 A lot of the noticing I’ve done has stemmed from my own experience of feeling unbearably trapped in my roles in various protocol systems and the process I have undergone (and am still undergoing) to see and understand the protocol systems I have inhabited and to make a deliberate choice about whether and how to stay in them. I have noticed common threads in my deconstruction efforts across multiple protocol systems in my life. My work on the Protocol System Experience knits together those threads.

Have questions like mine been examined before? Of course. This essay has echoes of sociology, anthropology, philosophy, psychology, economics, game theory, systems theory, and basically any field that deals with human behavior. Protocol systems are a foundational, cross-cutting concept, so will have been thought about a lot through many different lenses over time. Are there frameworks out there that overlap with mine? Undoubtedly. This project is an opportunity to describe what I see—to get it down on paper (screens) before I chicken out or get stuck in analysis paralysis.

Angela Walch is a writer, researcher, and creator based in San Antonio, Texas. She is a research associate at the UCL Centre for Blockchain Technologies. From 2012–2023, Walch was a Professor of Law at St. Mary’s University School of Law. Her research has focused on blockchain governance, systemic risks, blockchain language, and the intersection between these areas, through the lens of realism versus idealism. angelawalch.com

TABLE Protocol Archetypes

Guardians

Guardians are the performers of supportive protocol actions. As a cluster, they help the protocol system to grow and endure.

Auditor An Auditor assesses whether participants in a protocol system are complying with the protocol. There are generally protocols an Auditor has to follow to conduct their assessment with legitimacy (e.g. rules of accounting or rules of civil procedure or evidence).

examples: administrators conducting performance reviews, compliance departments in companies, Miss Manners and Emily Post, judges and juries, the Pharisees in the Bible

Booster A Booster acts to build loyalty to and enthusiasm for a particular protocol system. They may create and encourage rituals and practices to demonstrate membership in the system, such as holding pep rallies before a team sporting event; creating chants, songs, or oaths unique to the system; creating holidays to mark special people or historic events in the system; or creating special clothing or other markings unique to the system.

examples: cheerleaders, marketers, charismatic founders or gurus, the apostle Paul

Clinger Clingers resist change to existing protocol systems, whether in altering protocols or roles that people play. Clingers resist the creation of new protocol systems that could challenge or improve upon existing systems. Through their words and actions, Clingers live out Hume’s is-ought fallacy. Clingers fear change and hold tight to the familiar even if it is harmful to themselves or others. Clingers can be either Reapers or Fodder. Fodder may cling to the system in the hope that one day they may transition to Reapers.

examples: captain of the Titanic, originalist judges, Bitcoin Maximalists, people nostalgic for “the good old days”

Designer A Designer creates the protocols of a protocol system, embedding power dynamics and moral choices into the system. A Designer may be a Heretic, Rebel, Revolutionary, or Leaver from another protocol system.

examples: law-makers, policymakers, parties to contracts, founders of companies, mechanism designers in cryptoeconomic systems, some would say deities

Enforcer An Enforcer ensures that the protocols are followed by participants through whatever means. This could be through force, violence, the imposition of shame, taking resources, offering incentives, etc. Enforcers are the link between the Auditors and the Penitents in that they enact the decisions of the Auditors on the Penitents.

examples: police, prison operators, parents, assistant principals

Evangelist An Evangelist promotes the protocol system to Outsiders and encourages Outsiders to join the system. An Evangelist may or may not have awareness of or insight into the protocol system, and may sometimes be an Indoctrinator. Often, an Evangelist provides incentives for Outsiders to join the system.

examples: missionaries for religions, university admissions departments, participants in multi-level marketing schemes, employment recruiters.

Follower A Follower is in thrall to a protocol system itself, or to people with power, status, or high skill within protocol systems. Followers seek to follow protocol to the letter, whether by wearing required attire, watching only certain news channels, performing rituals so their team will win, or spending significant resources (time, money, health) to demonstrate their commitment. Followers may lack insight into the protocol systems they participate in. Because of their unquestioning commitment, they may be manipulated by Leaders or Reapers.

examples: Swifties, Deadheads, cult members, dedicated members of political parties, patriots, superfans of sports teams, highly rigid religious followers

Indoctrinator An Indoctrinator provides information about a protocol system to others that is deemed likely to proliferate the protocol system as it exists. An Indoctrinator is unlikely to provide information that is negative about a protocol system, may provide false or misleading information, and is unlikely to encourage critical thinking about the system or the information they provide.

examples: cult leaders, teachers of religious doctrine (sometimes), political party leaders

Influencer An Influencer shapes a person’s view of a protocol system or “the way the world is” (even if the influenced person does not have awareness of the protocol system), and may pressure / encourage them through various positive or negative consequences to join the protocol system, or to make certain decisions once they are a participant.

examples: parent, teacher, religious leader, mentor, boss, friend, recruiter

Maintainer A Maintainer acts as a caretaker of the protocol system, performing tasks necessary to keep the system operational. Though a Maintainer’s tasks are essential to the system, they often receive little glory, credit, or compensation for their work.

examples: protocol developers in blockchain systems, a nation’s armed forces, and women performing the emotional labor of remembering and leading family traditions like birthdays and holidays, administrators

Paragon A Paragon follows the protocol or has a reputation of following the protocol, regardless of the moral legitimacy of the protocol, and is held up as an example for others within the protocol system to follow.

examples: saints, the good son or daughter, a good student, an employee-of-the-month, the uber-wealthy in a capitalist system

Penitent A Penitent has broken protocol or is believed or portrayed to have broken protocol, and has accepted the consequences, regardless of whether they were not guilty of breach or the breach had moral legitimacy. Penitents serve as examples to other members of the system of what happens to protocol breakers, deterring others from breaking protocol themselves.

examples: Hester Prynne of The Scarlet Letter, a student in detention, a child being punished, or a person expelled from the protocol system

Scapegoat A Scapegoat takes the blame for negative outcomes suffered by participants in a protocol system, and often serves as a unifying force for the people blaming them. A Scapegoat can be either a participant in or an Outsider of the protocol system that blames them.

examples: the girls tried as witches in the Salem Witch Trials, Jews and others persecuted by the Nazis, avocado-toast-eating Millennials, resource-hogging Baby Boomers

Threats

Protocol archetypes can perform destructive protocol actions, acting to weaken or destroy a protocol system. We can call them threats.

Ally An Ally supports or aids (publicly or not) Fodder, Penitents, or Heretics. Allies may be Outsiders or participants in the protocol system.

examples: abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison or people who assisted in the Underground Railroad, male supporters of suffragettes, people who provide assistance to domestic violence victims, or a popular girl who stops her friends from bullying someone

Heretic A Heretic does not agree with the rules or practices of the protocol system and wants to either change the system or begin an alternative protocol system. Heretics risk everything—possibly their family, status, career, resources, and even their lives.

examples: Martin Luther, revolutionaries like those in the French, American, and Russian Revolutions, Albert Einstein, Martin Luther King, Gandhi, suffragettes, and Galileo

Leaver A Leaver exits their native protocol system, searching for a better situation elsewhere. This may be because of dysphoria suffered in their native system, a bad fit, or because better opportunities present themselves in alternative protocol systems. Being a Leaver may require abandoning resources, relationships, status, and more. In the refugee situation, exiting the native protocol system may not be by choice.

examples: immigrants who pursue a better life, refugees of war or famine, or people who come out as LGBTQ+

Dualists

Dualists are protocol archetypes who perform double-edged protocol actions. In some circumstances, the dualists strengthen a protocol system; in others they act as threats.

Soldier A Soldier protects the protocol system from Outsiders, takes resources from Outsiders for use by the protocol system, and uses force to make Outsiders join the protocol system. Their purpose is to defend and expand the protocol system. Some Soldiers volunteer for this, while others may be forced.

examples: corporate raiders, private equity funds, the military, the “muscle” that expanded empires like the Roman Empire, Mongol Empire, and the British Empire, mercenaries, Europeans who colonized the Americas

Educator An Educator provides information about a protocol system to others. An Educator may be inside or outside the system about which they educate. An Educator provides multiple points of view about the system, information about the system’s power structure, the history of the system from multiple perspectives, and the costs and benefits to those inside and outside the protocol system. Educators encourage their students to view the information they receive with a critical lens and to think for themselves.

examples: some teachers or professors, philosophers, Sages, Chiron, Dumbledore, Socrates

Leader A Leader has characteristics that draw people to listen to their recommendations or orders (depending on the protocol system structure), such as charisma, vigor, vision, or intelligence. A Leader inspires or compels participants to take actions that either support or undermine the protocol system. A Leader likely has awareness, and may or may not have insight regarding the protocol system.

examples: George Washington, Neville Chamberlain, Ann Richards, Boris Johnson, Adolf Hitler, Gandhi

Outsider An Outsider does not participate in a given protocol system. Outsiders offer alternative perspectives that can increase a participant’s awareness or insight regarding their own system. They can ask questions about practices of the protocol system that may prompt introspection and protocol examination in insiders. Even just meeting an Outsider may trigger awareness in a participant. Outsiders can function as Educators, even unintentionally.

examples: for a religious protocol system, someone from another religion or an atheist; for an American, someone from another country; Maria from Sound of Music

Hierarchics

Hierarchics are protocol archetypes who are defined by their place in the power structure of the protocol system

Flatterer A Flatterer fawns over those in positions of power or status within the protocol system, such as Leaders, Reapers, or Sages. They seek to be associated with power, often because of benefits they receive, such as status or wealth. Flatterers may overlook or hide flaws in those they flatter, and may defend them against legitimate criticism. Flatterers may seek to exercise power through those they flatter, and may engage in backstabbing or retribution against those they view as threats.

examples: craven politicians, kiss-ups, Spittleworth and Flapoon in The Ickabog, assistants to the head “mean girl”

Fodder Fodder lose more than they benefit from a protocol system. Often their sufferings or losses benefit others (Reapers) in the system, and they are akin to resources that are consumed by the Reapers. Fodder may become Heretics when they gain awareness or insight or when their suffering becomes too great.

examples: labor in a capitalist system, racial minorities in a system of white supremacy, women in a patriarchal society

Reaper Reapers are people who benefit more than they lose from the protocol system. They have more power and often more resources than other people within a common protocol system.

examples: men in a patriarchal system, whites in a system of white supremacy, owners of capital in a capitalist system

Consciousians

Consciousians are protocol archetypes who are defined by their awareness of and insight into the protocol system (their consciousness of it)

Abider Abiders have both insight and awareness, and are dysphoric in their role or w/ their protocol system at large. You might call them “conscious dysphorics.” Despite this, Abiders remain in their roles or in the larger protocol system.

examples: a spouse who doesn’t leave a toxic marriage, a professional who stays in their career despite misery, an LGBTQ+ person who does not live out their sexual orientation or gender expression

Floater A Floater is someone who lacks awareness of the protocol system they are participating in. They don’t see the water they swim in, so lack agency in the decisions they make regarding the protocol system.

examples: followers of every new clothing style, people pleasers, perfectionists, parents who haven’t thought through their parenting philosophy, heirs to fortunes

Hypocrite A Hypocrite has awareness of and insight into a protocol system, recognizes they’re in it, and presents themselves publicly as a Paragon even though they either (a) don’t follow the protocol, (b) understand that they are a Reaper exploiting Fodder, or (c) know they are a bad fit in their role or the protocol system.

examples: Joel Osteen, Lance Armstrong, Dennis Hastert, climate change activists flying on private jets

Learner A Learner is in the midst of gaining awareness of and insight into the protocol system. They may be guided by an Educator, a Sage, or an Influence, or may do the work of learning, deconstructing, and unlearning on their own. Learners are in a transition, or liminal, state as they move to higher levels of awareness or insight.

examples: most protagonists in literature/theater who are on their hero’s journey (à la Campbell), e.g., Harry Potter, Moana, Frodo, Ebenezer Scrooge

Sage A Sage has both awareness of and insight into a protocol system. They see that they are participating in it, understand their role in it, and have a deep understanding of the protocol system’s costs and benefits and power structures. A Sage is a lifelong Learner, keeps their awareness and insight up to date, and engages in self-reflection.

examples: Dumbledore, Gandalf, gurus, Mother Earth, Patches O’Houlihan in the movie Dodgeball, seasoned political advisors

-

1. “Multistable Perception,” ScienceDirect, Elsevier. www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/multistable-perception

-

2. Edgar Rubin, Synsoplevede figurer: studier i psykologisk analyse (Norway: Gyldendal, Nordisk forlag, 1915). www.google.com/books/edition/Synsoplevede_figurer/b4EeLO1WAAIC?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA30-IA3&printsec=frontcover

-

3. Mark J. P. Wolf, ed., World-Builders on World-Building: An Exploration of Subcreation (New York: Routledge, 2020).

-

4. It seems worth noting that in describing Edward VIII’s auto-enrollment in and later exodus from key protocol systems, I am not praising Edward’s actions, beliefs, or relationships (e.g., his potential support of Hitler and the Nazis).

-

5. Ben Johnson, “Kings and Queens of England & Britain,” Historic UK, n.d. www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/KingsQueensofBritain

-

6. Plenty of people would argue that protocols can also come from deities (e.g., the Ten Commandments; the Koran; see for example www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-33631745; or Aquinas’ natural law theory, ssrn.com/abstract=2197761) or exist in a kind of Platonic sense to be discovered by humans. And don’t even ask about protocols that are created by AI . . . that’s for another day.

-

7. In signaling how people within protocol systems should behave, protocols also embed requirements of belief in certain tenets (e.g., that capitalism is better than socialism or that a deity exists), but all that the system can really accomplish with regard to required beliefs is that participants behave as if they hold the required beliefs (e.g., by saying certain words, expending certain resources, or moving their body in certain ways). Defining protocols as simply signaling desired and undesired behaviors holds true.

-

8. Basically, go to any thesaurus and see how many synonyms there are for “rules” (e.g., www.thesaurus.com/browse/rule). It’s fair to ask whether I am just co-opting the word “protocol” and expanding its meaning to all the “oughts.” Have I made the protocol category now too big? Maybe. I think it’s useful, though, to try out categories at various levels of breadth and see what we can learn at each level.

-

9. Janna Tay, “A Phenomenology of Protocols,” Summer of Protocols (2023). summerofprotocols.com/research/a-phenomenology-of-protocols

-

10. Sarah Friend’s concept of “worlds” in her essay, Good Death, is another way of describing a protocol system. A “world” in her framework is what “grows on a protocol when a protocol lives.” summerofprotocols.com/research/good-death

-

11. Nadia Asparouhova, “Dangerous Protocols,” Summer of Protocols (2023). summerofprotocols.com/research/dangerous-protocols

-

12. I am telling myself that’s okay because this is a “thinkpiece” and not an academic paper . . .

-

13. Ryan Burge, Cafeteria Catholicism? How Many Catholics Agree with the Church’s Position on Hot Topics? (Graphs About Religion, May 2, 2024). www.graphsaboutreligion.com/p/cafeteria-catholicism

-

14. Andrew Kern, “Why the State Can’t Claim Our ‘Implied Consent,’” Mises Wire, October 16, 2019. mises.org/wire/why-state-cant-claim-our-implied-consen

-

15. For example, Stephanie Russell-Kraft and Casey Sullivan, “Widespread misery’: Why so many lawyers hate their jobs—and are desperate to quit,” Business Insider, June 23, 2022. www.businessinsider.com/lawyers-miserable-quit-hate-job-great-resignation-attorneys-2022-6

-

16. Paul Millerd, Pathless. newsletter.pathlesspath.com

-

17. Faith Hill, “The Parenting Prophecy,” The Antlantic, April 26, 2023. www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2023/04/parenting-acting-like-your-parents-breaking-cycle/673858/

-

18. Bridget Johnson, “Logo loyalty pushes middle school students to spend excessive amounts,” Fusion, February 1, 2022. maizenews.com/21584/news/logo-loyalty-pushes-middle-school-students-to-spend-excessive-amounts/

-

19. William Shakespeare, As You Like It, Jacques in Act II, Scene VII, Line 139.

-

20. I struggled with whether to use role or identity here. Role connotes more of an assigned part to play in a protocol system, while identity connotes an inherent part of the self. As Nadia Asparouhova writes in “Dangerous Protocols,” in protocol systems one’s role can become part of one’s identity, something you associate with who you are. A fundamental aspect of your self. I ultimately chose role for my framework because I want to highlight the possibility of a match or mismatch between the part you play in a protocol system and how you view your self.

-

21. Other thinkers refer to concepts analogous to protocol roles in domains like sociology, cultural anthropology, social psychology, self-help, economics, game theory, and philosophy.

-

22. No, they don’t kill you if you don’t get tenure, but they do cast you out of the university protocol system. Death is a possible consequence in protocol systems that impose the death penalty or engage in honor killings of those who don’t abide by protocols.

-

23. Asparouhova also explores this concept in “Dangerous Protocols,” arguing that once a protocol becomes ingrained and unseen (what she calls becoming implicit), people can view their compliance with an (unseen) protocol as part of their very identity.

-

24. I think a protocol system dies when people stop performing supportive protocol actions in relation to the system. Sarah Friend provides insights on protocol death and its process in “Good Death” (Summer of Protocols, 2023). summerofprotocols.com/research/good-death

-

25. Mariah Espada, “The True Story Behind the Duggar Family Docuseries Shiny Happy People,” Time, June 2, 2023. time.com/6284603/shiny-happy-people-duggar-family-true-story/

-

26. “Primogeniture and ultimogeniture,” Britannica, n.d. https://www.britannica.com/topic/primogeniture

-

27. Carl G. Jung, The Archetypes and The Collective Unconscious, trans. R. F. C. Hull (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1981).

-

28. Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1949).

-

29. Analogous frameworks to Pip’s Protocol System Journey would be Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey and Arnold Van Gennep’s 1909 Rites of Passage, describing the rituals accompanying status transitions across cultures.

-

30. Of course, this series of expected pre-marriage activities is a protocol system of its own.

-

31. As a former attorney and law professor, I would be interested to know how many people (like me) go to law school with a deep understanding of the requirements to get into law school (entry tests, recommendation letters, etc.), but only a shallow understanding of the good and bad parts of the legal profession and what it feels like to be an attorney. Based on personal and anecdotal experience, this seems pretty common in most graduate school enrollment decisions, even outside of law.

-

32. Jeffrey Danese, “This Is Water David Foster Wallace Commencement Speech,” May 2, 2022. www.youtube.com/watch?v=DCbGM4mqEVw

-

33. Youll Log, “Progressive—Becoming Your Parents,” January 17, 2021. www.youtube.com/watch?v=EfdrZzF_RL0

-

34. Faith Hill, “The Parenting Prophecy,” The Atlantic, April 26, 2023. www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2023/04/parenting-acting-like-your-parents-breaking-cycle/673858/

-

35. Of course, my definition of insight suggests that it is possible to gain knowledge to be able to understand the realities of a protocol system, rather than overstatements or myths or propaganda about it. In 2024, with a crisis of meaning and truth in full bloom, and an epic struggle between protocolized and Kara Kittel and Toby Shorin’s unprotocolized knowledge, the realities of any protocol system will be highly contested, meaning that it may be difficult for anyone to persuasively claim insight into any protocol system (Summer of Protocols, 2023). summerofprotocols.com/research/module-four/unprotocolized-knowledge

-

36. Jennifer Clarke, “Why did Harry and Meghan leave the Royal Family, and where do they get their money,” BBC, June 28, 2024. www.bbc.com/news/explainers-51047186

-

37. “Abdication of Edward VIII,” Wikipedia, last modified August 13, 2023. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abdication_of_Edward_VIII

-

38. Carl von Clausewitz, On War, 1836 (“war is the continuation of politics by other means.”)

-

39. “The Blob,” Wikipedia, last modified August 7, 2024. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Blob

-

40. Kaelyn R. Griffin, “An Examination of the Association of Religiosity, Purity Culture, and Religious Trauma with Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety” (master’s thesis, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, 2023). There are many support groups and podcasts about this topic, as well as numerous ones about religious trauma generally. digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations/4691/

-

41. As far as I know, we are not yet relying on AI for this, but that will be an interesting question to explore in future work.

© 2023 Ethereum Foundation. All contributions are the property of their respective authors and are used by Ethereum Foundation under license. All contributions are licensed by their respective authors under CC BY-NC 4.0. After 2026-12-13, all contributions will be licensed by their respective authors under CC BY 4.0. Learn more at: summerofprotocols.com/ccplus-license-2023

Summer of Protocols :: summerofprotocols.com

ISBN-13: 978-1-962872-25-6 print

ISBN-13: 978-1-962872-51-5 epub

Printed in the United States of America

Printing history: July 2024

Inquiries :: hello@summerofprotocols.com

Cover illustration by Midjourney :: prompt engineering by Josh Davis

«protocol archetypes, exploded technical diagram»