Dangerous Dating Protocols

Shreeda Segan

You’re put in a room with five strangers with the sole goal of finding a way to have fun together—in the shortest time possible. How do you solve this? It’s likely that you and the other strangers participating in this experiment come from different religious, ideological, and cultural groups. What’s funny to you will almost certainly not land as a joke with all five strangers. After all, you have no shared context with one another.1

The group chooses to play a game. A game has explicit rules. Once you have rules—and consensus around them—you can cooperate and compete with one another. Moments will occur when something is funny. Perhaps bad luck strikes you down despite all the care you’ve put into a strategy to win the game. Maybe someone accidentally fumbles a move—much like making a typo—yet has to pay the price because the game says their turn is over and the move sealed. The game, a protocol that quickly establishes a shared map and rules for navigating that map, rapidly creates a sufficiently shared context. As Venkatesh Rao says, a protocol creates new water in which we swim.2 Now fun can emerge where it otherwise couldn’t.

Why do we need protocols to date at all?

It’s no surprise that dating is another realm of human coordination that benefits from established protocols. Where a protocol is widely adopted, masses of otherwise unrelated humans can safely and productively interact with each other.

When playing a game (or making any decision), a player has to make a decision between the two strategies of exploration and exploitation.

Exploration involves trying out new options that may lead to better outcomes. Exploitation involves choosing the best-available option based on exploration. Finding the optimal balance between these two strategies is a crucial challenge in many decision-making situations, where the goal is to maximize long-term benefits.3

Too much exploitation risks getting stuck in a local minima. It’s likely that there are better solutions out there than you thought. Too much exploration, however, and you keep trying random new ideas without ever committing to one enough to see it through to completion.

Since the ideal strategy for many singles is to date around enough to find someone worthy of marrying, the “game” is of a finite length. At some point, singles will necessarily have to double down on a date, i.e., switch to exploitation. If you don’t date around (explore) at all, you may very well get stuck dating (or even marrying or having children with) someone you are incompatible with.

The problem of dating thus lies in finding and settling on a protocol that enables an optimal balance between exploration and exploitation.

A brief history of dating protocols

Humanity has not settled on a sustainable dating protocol that has established an ideal equilibrium between exploration and exploitation. It’s a shame as stable partnership correlates with better health and economic outcomes across the sexes.4, 5, 6, 7 Children of parents who are still married have better health, economic, educational, and behavioral outcomes. And

Being married changes people’s lifestyles and habits in ways that are personally and socially beneficial. Marriage is a “seedbed” of prosocial behavior.8

Marriage teaches you to care for another apart from yourself and to prioritize long-term collective well-being outside of short-term ones. A marriage is likely the most intimate relationship you have with someone outside of your immediate genetic kin.

The dating outcomes of billions of individuals hence determine the collective political and social commons that constitute our society. This is why dating is an important social issue whose protocols should be examined—and the consequences of such protocols taken seriously. Dysfunctional dating protocols have a profound ability to negatively impact the long-term progression of society. If you only care about interacting with others for short-term benefits you can extract from each other, you lose the potential for solving loneliness, building community, or accessing committed support systems. Society as a whole could become less resilient. The consequences of the behaviors of each generation impacts future generations.

In part, the lack of the emergence of a sustained, effective dating protocol is somewhat inevitable. Innovations in technology and culture will always change the broader environment within which any dating protocol has to prove its success, leading to the death of old protocols and the birth of new ones. But something that is not inevitable is the overemphasis on exploitation in traditional dating protocols. It’s a modern privilege to be able to entertain exploration as an option at all.

Arranged marriages, for instance, provide huge amounts of convenience, subverting the need to date at all. They have been the historic “protocol of choice” for South Asian, Middle Eastern, African, Jewish (primarily Ashkenazi and Sephardic), and other communities. Each of these cultures emphasizes the importance of family in decision making. Thus the parents and elders of young men and women typically look for intra-class matches with compatability assessed on the basis of shared religion, culture, and values. Physical attractiveness was not hyper-emphasized the way it is in contemporary dating. Arranged marriages also benefit from lowered expectations of conformity with romantic ideals, with partners instead prioritizing practical expectations and mutually beneficial arrangements around things like child-rearing and joint financial and household responsibilities.

However, arranged marriages skew heavily towards “exploitation.” By agreeing to marry someone early and with no period of dating, you forgo testing of on-the-ground compatibility. Red flag issues you may have otherwise discovered in a few months of dating become costly to escape. (Divorce is often looked down upon in the aforementioned cultures and, even if it weren’t, is still financially costly.) Further, many singles—especially single women—can become coerced or pressured into unfulfilling arranged marriages without consent. Subverting the arranged marriage protocol could lead to social death: your closest social networks (often family and family friends) shunning or shaming you forever. Even if an arranged marriage is not abusive and minimally viable, shouldn’t humans have the choice to explore a bit more to find matches that they might be better suited for? As Venkatesh Rao puts it,

protocolization is when things get more convenient, but you don’t have to give up additional political agency for it.9

While arranged marriages are more convenient in many ways than modern-day dating protocols, they are insufficiently “protocolized” because they often require major sacrifices of political agency.

Naturally, the development and increased access to contraception, abortion, and birth control reduced the stakes in pursuing sexual relationships. Previously, the fact that arranged marriages skipped the dating process was seen as advantageous. A child born in a marriage typically has more access to financial resources than a child born outside of one; fathers become legally responsible for child support if they out-earn mothers.

Therefore, derisking sexual relationships enabled more choice—exploration—in dating markets. New dating protocols emerged as market winners, including the prevalence of courtship and dating as concepts. The advent of cars and cheap entertainment venues such as dine-in theaters and social dance halls enabled the middle class to go on dates. The public nature of such venues further made women feel safe to go on such exploratory dates.

As women’s rights progressed, women acquired more legible negotiation power in relationships. They brought their own jobs, careers, and desires to their dating situations. The idea of dating to emphasize self-development—not just creating a stable environment for economic benefits, childrearing, and sexual relations—emerged. In other words, people discovered the benefits of romantic fulfillment. Relationships remain contingent until both parties sufficiently provide their worth and desirability to one another.

Serial monogamy also emerged as a common relationship pattern; people breaking up much more frequently in search of better relationships and pursuing a series of monogamous relationships. Still, most people settled down into marriage eventually, pulling the trigger on exploit mode.

The problem today’s daters face is that the mass adoption of online dating apps has not only eroded incentives to switch from explore to exploit mode, it has made exploration itself boring and dysfunctional.

Swiping now occupies a dysfunctional “protocol monopoly”

The birth of the consumer internet saw the birth of the first dating websites, like Match, eHarmony, and later, OkCupid. These sites allowed people to meet others outside of their existing networks. The first two were based on questionnaires and personality tests; the third introduced the first matchmaking algorithm.

These early websites became obsolete with the mass adoption of mobile phones. Since mobile phones enable location sharing, apps like the gay-male-focused Grindr were built to help people find potential sexual partners based on geographic proximity in a new form of dating known as geosocial dating. Profiles were largely image-based. Since members of the gay community occupy a sexual minority and are less likely to be legible to one another outside of sanctioned spaces like gay bars, geosocial dating enabled improved discoverability.

Tinder later adopted these same features but also introduced the notion of swiping—showing users only one profile at a time until a user decisively swiped left (rejected) or right (accepted). Since matches are only made once two users swipe right on one another, Tinder and its successors emphasize consent, permitting communication only between people who affirmatively agree to each another. Its adoption grew alongside (and perhaps amplified) the proliferation of hook-up culture—dating purely in exploratory mode, only as a means of sourcing sexual relationships.

Swiping worked since it addressed the labor costs of sifting through a large list of potential dates. Creating a sales-process-like funnel, a user has to consider only one person and one decision at a time (left or right?). It also gamified this decision making by rewarding users with matches. This basic app mechanic has proven to be sticky. Not only is Tinder the highest-grossing dating app, its basic swipe technology has been replicated by its top competitors (Hinge, Bumble).

The mass adoption of mobile phones led to the mass adoption of social media. This led to tons of online-first social interactions and, ultimately, the destigmatization of online dating. Online dating quickly went from something only the nerdiest did to becoming the common, default mode of finding dates.

For much of history, the most common way for people to meet each other was through mutual friends and shared social groups. Now, dating has been transformed into something akin to a pipeline process. In the same way that a sales rep sources leads, qualifies them, and then closes deals, people use apps to source dates. These dates either progress to later stages in the pipeline (kissing/hooking up, formally seeing one another, becoming a couple, and eventually, perhaps, getting engaged, then married) or eventually fail to (rejection). It’s also not uncommon for someone to be seeing multiple people at the same time, in the earlier stages of the dating pipeline, until one or a few are moved further along the pipeline.

But, as previously mentioned, dating apps fail to even enable successful exploration, i.e., the building of an effective sales funnel. When sales and marketing reps build and track sales pipelines, they use tools that allow them to populate potential leads in bulk, working in lists and spreadsheets. When it comes to dating, however, the most popular apps limit the number of new users someone can explore to just one at a time.

This brings us to a critical difference between sales and dating pipelines: the desired number of closed “deals.” Most people are dating to meet the one person they get married to. Sales reps, however, are trying to close the greatest number of deals.

Sales reps thus have a recurring need for the tools that help them source customers for their pipelines. This aligns with the incentives of the tool makers—often venture-backed software companies that need to demonstrate scale and recurring use.

Dating, on the other hand, is a flow market. Successfully navigating the market means exiting the market, i.e., successfully finding a relationship and no longer needing to look for one. It’s possible that the relationship fails and people re-enter and re-exit in the future. But the ideal, for many people, is to be able to find a thriving marriage and exit the market for good.

All of today’s popular dating apps were founded as venture-backed companies. It’s trivial to see how successfully matching people at the first attempt is not an ideal business outcome. Investors themselves openly reject the idea of funding dating apps that promise high chances of user success.10 By limiting the number of users you can see to one at a time, you can’t actually use dating apps to filter and search through large lists of people.

In other words, you can’t create a meaningful top-of-funnel for your dating pipeline. You’re seeing only what the algorithm recommends. The incentives of dating apps actively discourage building algorithms that show compatible matches, since finding a compatible match means you no longer need their product. You really are put in a room with total strangers, most likely the wrong kind, instead of those with similar interests and values. If you met the right stranger, you’d hit it off, get married, and exit the dating market altogether—making dating apps obsolete for you.

Yet these apps—through their clever gamification—have succeeded in capturing the majority of singles on the market. Onboarding to these apps is easy. You add a picture, a name, and a few simple details like age, location, and sexual preferences to start meeting users. Seeing who also swipes right on you satisfies curiosity and a basic human need for sexual validation. Carolina Bandinelli and Arturo Bandinello write,

. . . the match [is] not always or primarily instrumental to getting a date but rather as producing a form of satisfaction in its own right. [. . .] A match feels like a confidence-boost; it is a sign that the Other sees you and likes you [. . . ]. Admittedly, it is ephemeral, but it is also replicable, so the sense of void that follows the fleeting sense of satisfaction is rapidly filled up again, however temporarily, with another match.11

The use of swipe-based dating apps has also proliferated in part because there is no competitor with a comparably large user base. As we’ll see later, attempts to subvert swipe-based protocols all suffer from insufficient market liquidity. This is crucial as some degree of “protocol consensus” is necessary for dating protocols to work at all—enough people need to be aware of and bought into a protocol for the protocol to work.

All of the monetization features of dating apps are meant to increase your chances of successfully navigating the swipe right or left protocol. These features include allowing you to swipe on more people a day, attach a custom note or message to your profile as it appears on someone’s swipe stack, skip the queue of someone’s swipe stack, and show up first or actively indicate your interest (“superlike”) in the person when your profile appears on their stack.

Despite the success of dating apps in creating matches, whether the matches made on these apps are meaningful or conducive to long-term pair-bonding, is actively debatad.

Platforms make money by enabling one type of relationship and treating anyone looking for other types as noise in the system, leaving them underserved. The situation is similar to how LinkedIn helps recruiters search for talent but doesn’t help talent find jobs or meaningful connections.

When dating apps do work, it’s usually for users seeking hookups or short-term, casual relationships. Since hookups are noncommittal, users come back to the app(s) again and again to find more hookups. The apps win because they’ve generated recurring use. It’s also easier to find prospective hookup partners since hookup criteria are usually more superficial and easier to fulfill. (Is this person minimally attractive? Could I have sex with them for just one night?) Seeking a successful long-term relationship is much harder—you’re looking to find the one person who helps support or complement your self-actualization and growth needs for the long haul.

Even if you use dating apps to find a serious relationship, it’s harder to commit to getting to know someone or stick through moments of conflict when other matches and possibilities are just a few swipes away. Bandinelli and Bandinelli:

importantly, matches can be produced ab limitum, the underlying utopia being that of providing potentially infinite opportunities: a desire that gets constantly re-ignited, regardless of its object, and at the same time negated, as the next profile picture appears on the screen.12

Hence, dating apps actively discourage users from ever switching from pure exploration to exploitation.

Even in the realm of hookups, success is still lopsided. The Pareto principle (80/20 rule) states that 80% of the consequences come from 20% of causes. And it applies to dating: the top (i.e., most attractive) ~80% of women on dating apps compete for the top ~20% of men. Some men have openly written that unless you’re attractive, dating apps are a waste of time.13

Dating app algorithms also show a preference for attractive users (those receiving lots of likes and messages). Attractive users get more matches than they can meaningfully engage with. These users therefore put minimal effort into writing engaging messages. This practice of engaging with minimal effort then propagates as a norm across the entire ecosystem of dating app users.

And even if a hookup is what you’re after, matching with someone on an app is hardly a predictor of whether you’ll meet them in person, much less hook up. This is where dating apps fail to enable exploration!

Most matches fail. That’s because many of them don’t lead to conversation. And the ones that do start a conversation have a high rate of ghosting. This disincentivizes users from putting effort into their messages for getting to know someone. Says sociologist Greg Narr,

Through this process, the dating app assemblage becomes suffused with a boring mood that makes it hard for users to find substantial connections.15

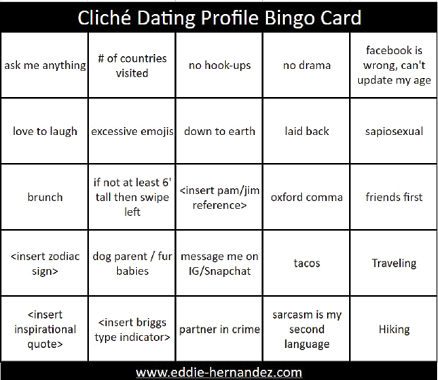

Even when an opening message or dating profile bio is successful at driving engagement yet nonspecific enough to attract a broad net of leads, it mimetically spreads across the ecosystem. Suddenly you have tons of men who’ve written the same “Looking for the Pam to my Jim,” profile title, further creating boredom.16 Dating is about looking for a unique connection, but, as we’ll see, dating protocol participants are incentivized to protocolize their own identities to better participate in the protocol. This is a type of flattening—sacrificing your dynamic identity in order to fit with the “flat” nature of digital dating apps, as currently conceived.17 You reduce yourself to Pam and Jim jokes to maximize matches while disregarding the compatability of those matches. Narr and Luong continue,

the mood of boredom fostered by dating apps represents a shift away from the rational market mentality scholars find on dating websites. [Instead,] dating apps seem to foster the boring, cynical engagement that critical algorithm scholars have argued is a central feature of data-driven capitalism.18

Dating websites, the predecessor of dating apps, were more successful in enabling users to navigate the dating pipeline process. OkCupid, prior to its own pivot towards a swipe-based mechanism, encouraged users to write customized, long-form biographies and answer survey questions about themselves. The survey answers were used to suggest compatible matches—not just the users who are the most attractive. The long-form biographies were searchable. You could signal interest in a niche sport, subculture, or band, and someone could search for those criteria and find users who fulfilled them, en masse. You could also message anyone on the service—without needing to be liked back first. There was also an ability to prioritize compatibility at the expense of distance. These features made dating websites effective tools in thoughtfully constructing a dating pipeline, even if the platform took more effort to use. There were more levers to push, and more ways to filter. And the platform did not gatekeep search or access. OkCupid was not hyper-opinionated about its protocol. It left users with sufficient freedom in how they interacted with the site, i.e., did not require them to sacrifice their political agency.

It is likely that early-day OkCupid came close to achieving a peak of harmony between exploration and exploitation motives. People mindfully made their picks from the apps but also took care to nurture these leads in-person (sometimes turning them into marriages or long-term friendships).

Unfortunately OkCupid succumbed to the pressures of monetization and scale. It was acquired by Match Group, which “owns and operates the largest global portfolio of popular online dating services,” including Tinder.19 Though OkCupid retained the features of long-form profiles and match percentage scores, it implemented swiping, stripped out many of its search features, and now requires a mutual match before messages can be sent.20 The company may have been pressured into making such changes in order to show the same scale and profitability as Tinder.

The last feature—mutual matching—is marketed as a safety feature, helping decrease the chance of unsolicited harassment. But, as a friend has said, “the problem is that the apps assume textual harassment is a worse problem for women than failure to actually meet anyone interesting.” Rather than introduce new technical patterns, the apps maintain the symmetrical nature of matching because matching is addictive.21

In the case of Bumble—which markets itself as a women-making-the-first-move app—mutual matching usually fails. Given the historical courtship protocol where men take initiative, men making the first move has become internalized as a cultural expectation. The introduction of a protocol where women must take the initiative requires a radical act of overturning these internalized norms. Sadly this is basically infeasible for the majority of people.

Most Bumble matches continue to fail to “convert.” Women also often get inundated with matches—more than they can keep up with. When women do message their matches, they may only say something minimal like “hi,” in order to pass the baton of meaningful initiative back to men. It’s interesting that, despite the introduction of a new technical women-make-the-first-move protocol, most users find a way to sidestep the rules in order to revert back to pre-established norms.

Dating apps thus transform users’ desires for enduring romantic relationships into desires that can instead be satisfied in alignment with the goals of data-driven capitalism: seeking sexual validation and collecting many speculative sexual futures—at the expense of actually finding a viable relationship.

Current geosocial, app-based swiping dating protocols have thus captured the dating market yet fail to deliver on creating relationships at a meaningful rate. They form an entrenched protocol monopoly despite being entirely dysfunctional on both exploration and exploitation.

Attempts to subvert the protocol monopoly

Swiping protocols control how and when data is shown to users. They pre-filter people and dictate what someone’s daily swipe stack is. Many approaches have cropped up in recent years to subvert the swipe protocol monopoly but ultimately failed. (See table.)

Others try to outsource the search to matchmakers. The buzz surrounding Netflix’s recently published shows, Indian Matchmaking and Jewish Matchmaking, could be an indication of a growing cultural interest in a simplified dating protocol where the pipeline is built by a trusted matchmaker. However, the shows are demographic-specific, indicating a mismatch between American cultural protocols and the matchmaking protocol. The latter relies on strong communal networks and near-religious levels of belief in the sanctity of marriage to really work. Still, digital arranged marriage platforms like Parents Matchmaking22 are taking off in cultures where arranged marriages once succeeded.23 Again, this approach overindexes on exploitation.

Today platforms like Tawkify24 are selling digital matchmaking as a service. And Keeper25 says its matchmaking is largely driven by AI and relationship science—an attempt to automate matchmaking as much as possible, with minimal reliance on expensive human matchmaking labor. It remains to be seen if these products will reach sufficient protocol consensus26 or work as business models. Perhaps they are a response to a collective plea for help in a more choiceless direction—swinging the pendulum too far back towards exploitation again, i.e., outsourcing the work of finding a suitable partner to a matchmaker à la arranged marriages.

There’s also increased interest in a close cousin of arranged marriages—the “trad” (traditional) lifestyle.

A tradwife (a neologism for traditional wife or traditional housewife), in recent Western culture, typically denotes a woman who believes in traditional sex roles and a traditional marriage.27

The rigid and gendered roles and expectations within trad relationships attempt to avoid the negotiation process inherent in the modern ideal of love relationships based on equality. One needs only to find a minimally qualified prospective life partner to agree to commit to such a lifestyle. In reality, however, the premise of finding a minimally qualified partner is false in the current cultural context. It was only possible to have a tradwife during a brief period of U.S. history when the country had so much wealth that men could support a family on one salary.28

Today, the trad movement demands much from prospective tradwives: no tattoos, a certain race and weight, having minimal previous sexual partners, and dressing and acting in anachronistic ways no longer appropriate in general Western culture. The tradwife has become a scarce commodity. Becoming a tradwife is also costly—meeting the criteria for an partner at the expense of transacting with the broader world. The trad protocol is also insufficiently protocolized,29 per the definition by Venkatesh Rao cited earlier, since it offers convenience at the clear expense of tradwives’ political agency.

Tradwife seekers often fail to find a suitable partner because of overfitting: having so many criteria they filter for that they source effectively no leads at all. No leads means you have no ability to create a pipeline to explore nor exploit. The trad life will continue to have insufficient protocol consensus unless the broader culture also changes to accommodate it. It is merely a fantasy.

It’s sad that many of these attempts at subverting swipe-based protocols fail. Several others have resorted to “exiting” dating protocols altogether: making no active effort to solicit dates and instead choosing to rely entirely on serendipity.

Today’s protocol monopoly is dangerous

In an essay, Nadia Asparouhova introduces the idea that protocols are neither good, nor bad, but dangerous.30 She argues that protocols “do not liberate us, but rather control us completely” and

protocols demand not just our compliance, but our loyalty in relinquishing our decision-making power to a formless entity.

More critically, however, she stresses that

because protocols are not owned or mediated by a central authority, if you don’t like the protocol you’re in, escape is not as “easy” as switching platforms.

Indeed, the swipe-based protocol is not in itself owned by a central authority. And yet it occupies a protocol monopoly. Match Group owns more dating apps than any other company. If you switch to another dating platform with sufficient market liquidity—as in switching from Tinder to Hinge or Hinge to Bumble—you’re still stuck with the swipe protocol. The apps outside of Match Group (e.g., Bumble, Coffee Meets Bagel) must also submit to the monopoly form (swipe protocols) for users to onboard with ease. People eventually expect their apps to use the swipe protocol they’ve become used to. The dating-app industry is an example of how a monopoly interest can push a protocol on the masses while simultaneously disavowing their responsibility for it. Match has recently launched a new campaign advertising itself as the “dating app for adults” despite changing nothing at the technical protocol layer.31

One might wonder why protocol participants get stuck in a protocol monopoly at all. This is touched upon earlier: the way the current market for startups (venture-backed) is designed creates incentives for businesses (agents) that are at odds with the interests of daters (principals). This is a standard principal-agent problem:

conflict in interests and priorities that arises when one person or entity (the “agent”) takes actions on behalf of another person or entity (the “principal”).32

A dysfunctional macro-level market design permits incentive misalignment and even market capture. “The dating app market made $4.94 billion revenue in 2022, $3.1 billion came from Match Group”33 which owns Tinder, Hinge, Match, OkCupid, Plenty of Fish, and other dating apps. Network effects rule the dating app industry. If one company can get enough market share, they implicitly force the others to adopt the same protocol (with minor tweaks) because enough people come to believe that this is just how dating is.

Asparouhova also introduces the Kafka Index, a set of evaluative criteria for identifying bad protocols.34 Applying the index to swipe protocols, we find that it is quite kafkaesque. Today’s dating protocols don’t fit all of Asparouhova’s criteria for bad protocols. She goes on to describe how some protocols are stable yet suboptimal, and how

[b]eing trapped in protocols dictated by a functional-yet-suboptimal system feels eerily calm, yet unsatisfying. Everything works, sort of, but participants feel a curious lack of fulfillment. (Remember that protocols are designed to accomplish a function, but not a purpose.)

Contemporary dating protocols fit this category of stable yet suboptimal protocols well. They fulfill the function of creating matches but the market in which they operate does not incentivize them to fulfill one of the largest purposes of using dating apps: finding a meaningful, long-term relationship.

Sadly people then approach dating apps with the intent of maximizing the outcome of this function but not fulfilling their original purpose. They have solved conversations—using generic pickup lines and witty jokes that drive engagement—with a mass audience of matches. But dating to find a meaningful relationship is about catering to yourself and a prospective partner as specific, unique people.35

Asparouhova posits that there are four types of protocolization. A protocol can go from being introduced as hard infrastructure, to having legible explicit rules, to being characterized by implicit rules (i.e., norms), to being internalized at the level of personal identity. Protocols shift into and out of these types at different stages in their lifecycle.

Today, people have started to internalize swipe-based protocols into their personal identities: they retool their dating desires, standards, and behaviors to fit what the protocol offers. They approach dating apps in a generic, mimetic way to drive up their matches. Perhaps they also start to shift their wants to what the dating app offers—hookups and noncommittal relationships—since those outcomes are what are readily available. This shift is of course encouraged by the perception of an unlimited dating pool—there are apparently infinitely more matches to be found just a few swipes away. This makes it less compelling to ever settle on one person to commit to.

Since there is a general lack of protocol legibility in the world, protocols can operate in dangerous ways when their presence becomes so implicit that people change their desires and behaviors to fit them. Ideally, protocols should serve us. They should be designed to fit our desires. We shouldn’t mindlessly redesign ourselves to fit them.

Imagining meaningful alternatives for today’s dating protocols

To create better dating protocols, there is a need for a fair market for building protocols that align with user incentives. A well-designed protocol economy could accomplish this. One of the primary goals of the blockchain sector, I believe, is to make principal-agent problems legible, for example by having transparently designed smart contracts serve as agents in place of traditional agents like businesses, people, or platforms.

Blockchains protocolize the agent in the principal-agent problem. Much of the industry’s mission could be described as protocolizing markets to become more free and just. Such markets could restore economic rationality to dating. Society could make progress toward finding a balance between exploration and exploitation in dating. We may see many experiments emerge in this area, some of which I describe below.

Decentralized dating protocols

Decentralized social media protocols like Farcaster, Bluesky, and Nostr are open protocols with many client apps. All data on the protocol is publicly and freely available. Interested developers can build their own client app for accessing, creating, and interacting with this data. These protocols are attractive partly for their resistance to capture by centralizing forces. There’s no single algorithm controlling everyone’s experience of or access to data on the protocol.

A decentralized dating protocol would allow users to create one profile and then choose and use a variety of client apps to find the profiles of others. And if you don’t like someone else’s dating client protocol, you can invent your own and ingest everyone else’s data since that data will be interoperable. This directly fixes the protocol monopoly problem we see today in swipe-based protocols. Any dating app client built on the decentralized dating app protocol would have access to market liquidity and a fair shot at competing within the same pool of users.

While decentralized social media platforms allow users to choose or control how content is temporally shown in a timeline, a decentralized dating platform would allow users to choose or control how prospective dates are searched and filtered for.

The hope is that a decentralized meta-dating protocol would once again reinstate the rational market mentality required to effectively author and navigate one’s own dating pipeline. It would also actively prevent the creation of companies like Match Group (which controls several dating apps.)

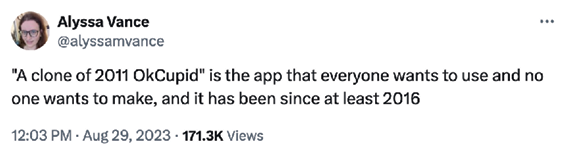

Recreating the old OkCupid

Recreating the old OkCupid in the form it existed before its acquisition by Match Group is something that many people want36 and would be an example of a client app that could flourish in a decentralized dating app market.

Date me docs are effectively a plea for a recreated OkCupid built around longer descriptions. But no one has the resources to rebuild the rest of the infrastructure around these descriptions, such as personality questions for ranking by values-driven compatibility or a filtering mechanism that allows search for keyword matches in people’s profile texts. My suspicion is that anyone who could build such a service knows that such an app would die in the current market.

Reintroducing secondary networks to “unflatten” dating protocols

When dating apps go digital, they emphasize certain affordances (accessing a volume of matches in a geosocial manner) at the expense of others (leveraging localized network ties). Locality impedes volume and restricts geographies. Digital dating apps also “flatten” some of the dynamics inherent to in-person dating.

But in giving up locality, we no longer have secondary relationships to maintain with the people who make date recommendations. We don’t have “skin in the game” to behave graciously and consider committing to dates that our local network suggests to us because other options are “just a swipe away.”

What if dating apps introduced local ties but with the “locality” defined in relation to our digital networks? What if we were able to date within the first, second, and possibly even third-degree networks of our social media mutuals? (And maybe add a secondary filter for only those connections within a geographic range?) What if our social graph apps integrated seamlessly with our dating apps? We would draw from what has historically otherwise worked—dating someone you meet through friends or family—without sacrificing the benefits of exploration.

AI dating

AI could help automate and expedite some of the onerous pipeline processing. A bot version of you could message and match with other people or, better yet, their own bot versions. You could then review recommendations and sample chat logs to see what interacting with someone might be like with a reduced emotional and energy investment.

AI dating could help make people’s stated versus revealed preferences clearer to them too. Your bot could make a bet on someone who is somewhat interesting but not your exact type. Exact chemistry is hard to predict. AI dating could de-risk taking chances on people, and help illuminate what types of people you might actually prefer.

Since many of the fears surrounding relinquishing one’s work to AI involve issues of trust, decentralization could again play a role in making AI protocol participants feel safer experimenting with such protocols.

Your AI bots could also go on a trial “blind date” with one another. If the AI bots find themselves compatible, they could use zero-knowledge cryptography to transmit the stamp-of-approval to you (without giving anything away about how it might go), so you could have an in-person date with a higher-than-trivial degree of confidence that it will go well.

————

Protocols can operate in dangerous ways when their presence becomes so implicit that people change their desires and behaviors to fit them. Ideally, protocols should serve us. We shouldn’t mindlessly redesign ourselves to fit them. Instead, we should intentionally design them to fit our needs better—perhaps starting with a reinvention of dating protocols. Δ

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thank you to Summer of Protocols, with a special thanks to Nadia Asparouhova, Alice Noujam, Venkatesh Rao, Tim Beiko, Rafa Fernandez, Shuya Gong, Drew Austin, and Saffron Huang who all took part in the development of my ideas. Also thanks to my friends David, Lisa Neigut, Avi Glozman, Chelsea Savit, Raymond Zhong, Sachin Benny, Gabriel Duquette, Tasshin Fogleman, Jake Naviasky, and Anonymous for their contributions.

SHREEDA SEGAN has been an editorial writer at Meridian where she covered web3, entrepreneurship, and generally what it means to be a founder. She also participates in weekly governance studies calls at Yak Collective. shreedasegan.com

1. Disclaimer: This work focuses on cis, straight, monogamous relationships in the West. Dating is a huge topic that intersects with gender and sexual theory and with religious and political values. I’m attempting to address the failures of current dating protocols in serving a specific market of daters, those looking for heteronormative long-term stable partnerships (often taking the form of marriage) in the West. I look forward to seeing research on dating protocols in diverse markets.

2. Venkatesh Rao, “Magic, Mundanity and Deep Protocolization: The next world-transformation process is here,” Ribbonfarm Studio, July 1, 2023. studio.ribbonfarm.com/p/magic-mundanity-and-deep-protocolization

3. Wikipedia, “Exploration-exploitation dilemma,” n.d. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exploration-exploitation_dilemma

4. Elizabeth Matsangou, “For richer for poorer: the economics of marriage,” World Finance, n.d. www.worldfinance.com/wealth-management/for-richer-for-poorer-the-economics-of-marriage

5. Julie Fredrickson, Twitter, August 30, 2023. twitter.com/almostmedia/status/1696965037133541670

6. Jennifer Chen, “The Connection Between a Healthy Marriage and a Healthy Heart,” Yale Medicine, February 7, 2018. www.yalemedicine.org/news/healthy-marriage-healthy-heart

7. Wikipedia, “Marriage and health,” n.d. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marriage_and_health

8. United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, “What Are the Social Benefits of Marriage?” For Your Marriage, n.d. www.foryourmarriage.org/blogs/social-benefits-marriage/

9. Rao, “Magic, Mundanity and Deep Protocolization.”

10. immad, Twitter, July 9, 2023, twitter.com/immad/status/1678208955988733954

11. Carolina Bandinelli and Arturo Bandinelli, “What does the app want? A psychoanalytic interpretation of dating apps’ libidinal economy,” Psychoanalysis, Culture & Society, Vol. 26 (2021), pp. 190.

doi.org/10.1057/s41282-021-00217-5

12. Bandinelli and Bandinelli, p190.

13. worst-online-dater, “Dating apps are mostly a waste of time for guys unless you are really hot and the rest of us will all die sad and alone — a quantitative socio-economic study: Hinge Edition,” Medium, November 14, 2022. medium.com/@worstonlinedater/dating-apps-are-mostly-a-waste-of-time-for-guys-unless-you-are-really-hot-and-the-rest-of-us-will-9b65c3bd0b88

14. Eddie Hernandez, “Cliché Dating App Profiles: Headlines, Examples & Quotes,” July 5, 2022. eddie-hernandez.com/cliche-dating-profile-bingo-card/

15. Gregory Narr and Anh Luong, “Bored Ghosts in the Dating App Assemblage: How Dating App Algorithms Couple Ghosting Behaviors with a Suffuse Mood of Boredom,” SSRN, December 4, 2021. dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4233502

16. whatever9_, Reddit comment, 2020. www.reddit.com/r/Bumble/comments/g6a7l6/looking_for_the_pam_to_my_jimalmost_every_guy_on/

17. Alexandre Borba Da Silveira, Norberto Hoppen, and Patricia Kinast De Camillis, “Flattening Relations in the Sharing Economy: A Framework to Analyze Users, Digital Platforms, and Providers,” in Handbook of Research on the Platform Economy and the Evolution of E-Commerce, edited by Myriam Ertz (Hersey, Penn.: IGI Global, 2022). doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-7545-1.ch002

18. Narr and Luong, p. 6.

19. Wikipedia, “Match Group,” n.d. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Match_Group

20. See @simpolism, Twitter thread, December 22, 2017, for a breakdown on the changes it implemented. twitter.com/simpolism/status/944284443342143489

21. Brooke Keaton, “How Dating Apps Use the Design Features of Slots to Keep Reeling You In,” Casino.org, February 12, 2020. www.casino.org/blog/how-dating-apps-copied-slots/

23. Viola Zhou, “Desperate Chinese parents are joining dating apps to marry off their adult children,” Rest of World, August 3, 2023. restofworld.org/2023/parent-facing-matchmaking-apps-china/

24. Tawkify. tawkify.com

26. I define protocol consensus as “enough people, at scale, aware of and engaged with a protocol for the protocol to work.”

27. Wikipedia, “Tradwife,” n.d. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tradwife

28. Exploros Article Summary, “Economy in the 1950s,” n.d. www.exploros.com/summary/Economy-in-the-1950s#:~:text=The%20Decade%20of%20Prosperity,to%20balance%20the%20federal%20budget

29. Rao, “Magic, Mundanity and Deep Protocolization.”

30. Nadia Asparouhova, “Dangerous Protocols,” Summer of Protocols, 2023. summerofprotocols.com/research/dangerous-protocols

31. Tim Nudd, “Match Launches ‘Adults Wanted’ Campaign in a Dating Scene Where They’re in Short Supply,” Ad Age, May 30, 2023. adage.com/creativity/work/match-launches-adults-wanted-campaign-dating-scene-where-theyre-short-supply/2497291

32. Wikipedia, “Principal–agent problem,” n.d. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Principal%E2%80%93agent_problem

33. David Curry, “Dating App Revenue and Usage Statistics,” Business of Apps, March 12, 2024. www.businessofapps.com/data/dating-app-market/

34. Asparouhova, “Dangerous Protocols.”

35. Asparouhova, “Dangerous Protocols.”

36. Alyssa Vance, tweet, August 29, 2023. twitter.com/alyssamvance/status/1696554182302384199

Protocol subversion approaches

|

Method of subversion |

What they offer |

How they fail |

|

Speed dating, e.g., Hidden Gems—speed dating marketed towards “meet[ing] authentic singles in person.” |

Guaranteed in-person encounter |

Cannot filter through people, i.e., have to commit to a speed date with them, doesn’t scale well—can only speed date so many people in one evening |

|

Sanctioned in-person courtship |

Guaranteed in-person encounter |

Insufficient protocol consensus around using this protocol |

|

Gaming the dating app algorithm itself, |

Reclaiming control from dating app algorithms; gamifying one’s “attractiveness” |

Still working within the limitations of how other people approach these apps (with minimal effort and low expectations of conversion to in-person encounter) |

|

Date-me docs, i.e., homebrew dating profiles published on personal websites, e.g., the dating docs of the rationalist community. www.nytimes.com/2023/08/02/style/date-me-docs.html |

Reclaiming control from dating app algorithms |

Insufficient protocol consensus around using this protocol; difficult onboarding and discoverability |

© 2023 Ethereum Foundation. All contributions are the property of their respective authors and are used by Ethereum Foundation under license. All contributions are licensed by their respective authors under CC BY-NC 4.0. After 2026-12-13, all contributions will be licensed by their respective authors under CC BY 4.0. Learn more at: summerofprotocols.com/ccplus-license-2023

Summer of Protocols :: summerofprotocols.com

ISBN-13: 978-1-962872-12-6 print

ISBN-13: 978-1-962872-38-6 epub

Printed in the United States of America

Printing history: February 2024

Inquiries :: hello@summerofprotocols.com

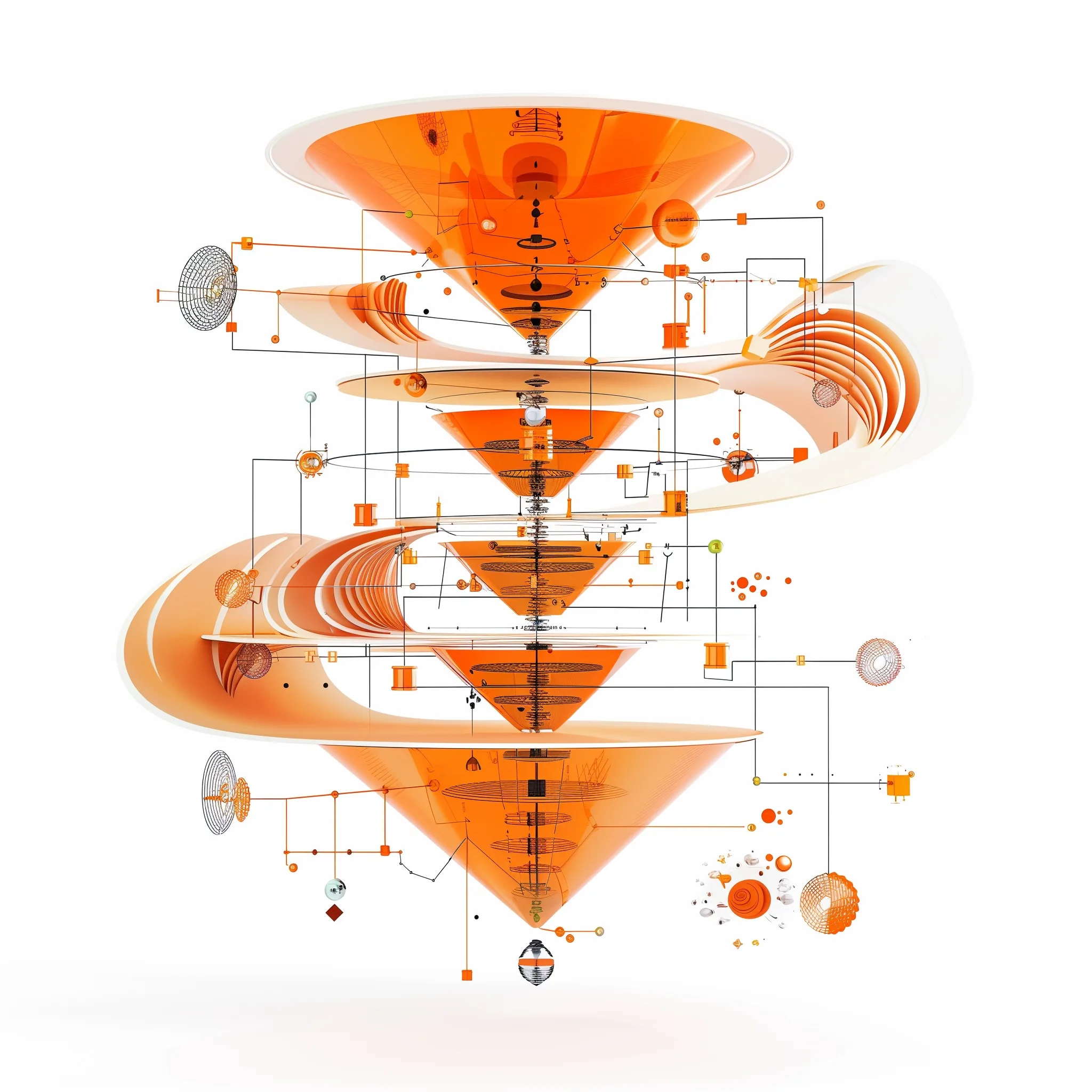

Cover illustration by Midjourney :: prompt engineering by Josh Davis

«dating funnel, exploded technical diagram»