Good Death

Sarah Friend

In a Reddit thread called “When is an MMO considered ‘dead’ to you?” user UnoriginalAnomalies asks,

I’m curious at what point people start actually considering a game “dead.” What’s your threshold?1

MMO, a shortened version of the acronym MMORPG—massively multiplayer online role-playing game—encompasses a broad set of online games featuring a persistent world and player avatars. In the Reddit responses to the post, users respond with criteria they find meaningful: when the game studio downsizes their staff; when there are no more updates from the developer; when there is no one at the spawning area. Across this thread and two similar threads like “What constitutes a ‘dead MMO’?”2 and “The Signs: How do you know if an MMO is dying?”3 are 177 replies offering other criteria, different combinations, and counterexamples.

Can a protocol die? If a protocol is alive, it lives the way a mall does—through the activity of its participants—and dies by metaphor. What overarching term can we apply to these entities, living or dead? I propose worlds, building on Ian Cheng in Worlding Raga: 2—What Is a World?

We could say a World is something like a gated garden. A World has borders. A World has laws. A World has values. A World has dysfunction. A World can grow up. A World has members who live in it . . . A World manifests evidence of itself in its members, emissaries, symbols, tangible artifacts, and media, yet it is always something more.4

A world grows on top of a protocol when the protocol lives. Platforms, places, books, TV shows, video games, or philosophical movements can also generate worlds. One might call a nation a world. A world is an ecosystem of avatars, grown through their time and attention. Not every protocol can die because not every protocol lived, as a world, in the first place.

What do we mean when we refer to a world as dead? Most of these dead worlds still exist. MMOs that are not shut down by the developers can linger indefinitely. The mall we call dead has not been demolished. I can still log into my LiveJournal. Nonetheless, these things have changed state. When we use death as a metaphor, as is often the case with metaphors, we reveal a truth that is difficult to articulate otherwise: something is gone. And much like death in more familiar contexts, it cannot be recovered.

Sometimes, a world has a legitimate, planned funereal moment. In 2008, Electronic Arts decided to shut down the servers of The Sims Online, a multiplayer version of the classic single player simulator—scheduling an apocalypse for the world and all of its community members. In the final minutes of the game, players gathered in the town hall where one of the community members gave an emotional final speech:

I just wanna thank you all, it’s been an amazing experience, it really has, and I told myself I wouldn’t make myself cry, but I can’t stress enough how much you guys have meant to me over the past, oh, however many years it’s been.5

Another example is Asheron’s Call, which ran from 1999 to 2017. The game had a strong and dedicated community of players, but the number of active users had shrunk over the years and the game was no longer profitable.6 In a video documenting the final moments, as player avatars disappear, one streamer says, through tears:

Don’t let Dereth go to waste. And all these people and all their items. And everything that we’ve worked for, the friendships, and the relationships, and the marriages and the kids and the friends and everything that people have had. Don’t let this go to waste. Thank you everyone.7

In these moments of grief we can see—perhaps more than at any other time—what characterizes the life of these worlds. Protocols live through attention; they die from neglect. This attention leaves its most noticeable fingerprints in the social lives of digital worlds. Like The Velveteen Rabbit, Margery Williams’ classic children’s story about a toy that comes to life, they have been loved into a kind of transubstantiation:

“Real isn’t how you are made,” said the Skin Horse. “It’s a thing that happens to you. When a child loves you for a long, long time, not just to play with, but REALLY loves you, then you become Real.”

“Does it hurt?” asked the Rabbit.

“Sometimes,” said the Skin Horse, for he was always truthful.8

The emotional investment and the participation of living beings in a world is not obviously quantifiable, but it has reality—and this quality is not unique to games. The first marriage vows on a blockchain were enshrined in 2014 by David Mondrous and Joyce Mondrous.9 The first blockchain-based memorial is from 2011, to Len Sassaman, cryptographer and privacy advocate, using ASCII art on the Bitcoin network.10 In 2015, an early project on the Ethereum network that allowed people to record short messages called Terra Nullius hosted a memorial message to Nóirín Plunkett, opensource contributor and at the time of their death vice president of the Apache Software Foundation.11 In 2020, a smart contract was deployed to serve as a memorial for coronavirus whistleblower Dr. Wenliang Li.12

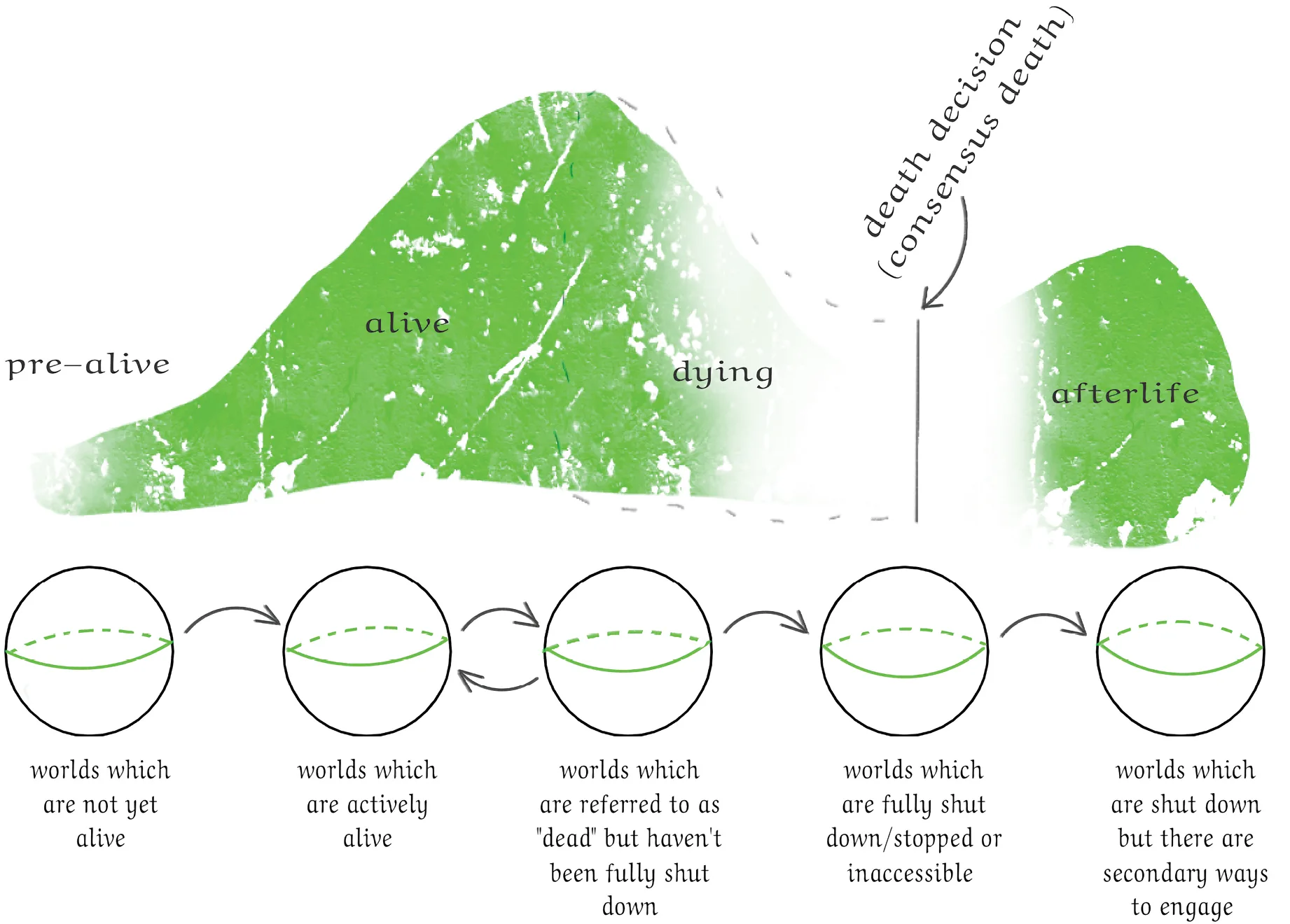

Many MMOs that have lost their rich player community, matching the Reddit descriptions, are better described as being in a liminal state between alive and dead—something like a protracted dying. Sometimes a world will appear to be dying, then come back to life. While a world is dying, one can argue about its relative deadness or debate different death criteria. At some point in the lifecycle, the liminal state ends—in the case of an MMO, the end usually looks like its developer going out of business or making the decision to no longer maintain the servers—and the world reaches consensus death. An afterlife for an MMO could look like an unofficial community-run version; if successful, the new version could eventually become a world of its own. In general, the end of the dying process takes the shape of a decision, consensus death, undertaken by an authority or marked by ritual.

Figure 1. The Lifecycle of a World

Diagramming the lifecycle of a world, we find something like Figure 1. Following this observation, we will discuss two alternate understandings of death and how they apply in a protocol context.

First, death-as-a-process: death is not a simple binary transition, instead it is a process (dying) that may result in a protracted liminal state between alive and dead. This liminal state is sometimes understood as transitional and characterized by possible disagreement or ontological uncertainty about relative liveness or deadness.

The death-process ends with the second key hallmark of death as it will be discussed here: death-as-a-decision. Death is not a given, nor is it a clear natural fact—death is instead a decision, similar to a diagnosis, with domain-specific criteria determined by technology, authority, and culture. We can further separate death-as-a-decision into cases where the world has a clear decisionmaker, such as an MMO or platform, and cases where there is not, such as a peer-to-peer protocol.

Neither death-as-a-process nor death-as-a-decision are unique affordances of worlds. Even in the non-digital context or cases where death appears to be clearly delineated, such as the death of humans, we find a similar structure. Not only in the medical profession, but also spanning spiritual understandings, funerary rituals, and the legal system, decision-making protocols surrounding death allow or even require a lengthy liminal space or process.

In Twice Dead: Organ Transplants and the Reinvention of Death, Margaret M. Lock recounts the changing criteria of human death over the 19th and 20th centuries.13 In the late 1800s, diagnosing death was considered medically difficult, with some doctors insisting the only inarguable marker of death was the beginning of putrefaction. Public anxiety spread about being buried alive, epitomized in a book called Premature Burial, and How It May Be Prevented.14 Over the course of the 19th century, as death became increasingly a medical and not religious event, doctors sought ever-more precise ways to judge the moment of death. In the late 20th century, with changing medical technology—notably the mechanical ventilator—it became possible to diagnose brain death separately from (and before) the collapse of other physical systems. With current capabilities, a body can continue in brain-dead stasis for years.

And yet, even with contemporary technology and its unprecedented access to the body, clear consensus around brain death as legitimate death are not global universals. In Japan, a country where access to medical technology is at least as widespread and advanced as the United States, situating the brain as the sole location of personal death is controversial. Lock observes:

Efforts to assign death scientifically to a specific moment are frequently rejected outright by both medical and lay people. Dying is widely understood as a process, and cannot therefore be isolated as a moment. What is more, the cognitive status of the patient is of secondary importance for most people.15

Moreover:

Even though Japanese neurologists concur about the irreversibility of brain death, and the vast majority of them are convinced that they can diagnose this condition reliably, they nevertheless remain reluctant to cooperate with organ procurement. Even now, many hesitate to encourage relatives to think of brain-dead patients as dead.16

The hardest evidence of this differing ontology of death is the differing frequency of organ donation in both locations, since organ donation relies on both social and legal consensus that a brain dead person is dead. In the United States, deceased organ donors per million of the population is 36.88. In Japan, the number is 0.99.17

Further, in the legal and statutory context, there are many cases where death is understood to exist separately from the body, leading to protracted liminal states. In most jurisdictions, there are protocols for eventually coming to consensus about whether an absent or missing person is dead. In the United States, if the person was not exposed to “imminent peril” (a plane crash or similar) it usually takes seven years. In some jurisdictions such as Poland and Germany, it can take as long as ten years. In this intermediary period, the missing or absent person is, while likely physically dead, still legally alive—their beneficiaries cannot collect life insurance and their estate cannot be administered. It’s estimated between 60,000 and 100,000 people are in this legal liminal state in the United States alone.18 The converse can also happen, where someone is declared legally dead but is in fact alive, sometimes as part of a scam or identity theft and sometimes by administrative error. Both cases reveal the decisionmaking practices around death and provide useful edge cases for thinking about what it is exactly that dies—a body, a legal entity, a social being, something else?

In Celebrations of Death: The Anthropology of Mortuary Ritual, Peter Metcalf and Richard Huntington use the framework of “rites of passage” to examine death rituals.19 The term rite of passage was coined by ethnographer Arnold van Gennep, in a 1909 book of the same name, where it is applied to pregnancy, childbirth, initiation, betrothal, marriage, and funerals.20 He characterizes a rite of passage as being a transition from one state to another and as having three phases: separation (from the previous state), liminality (being between states), and incorporation (into the new state).21

Metcalf and Huntington follow this with an extended analysis of cultures where there is secondary processing of the corpse, namely, an initial ritual, followed by a lengthy intermediary period consisting of months to as much as five years, after which the corpse is exhumed and a further ritual concludes the death process.22 They focus their analysis on Indonesia, where “many people conceive of a period when the mortal is neither fully alive nor finally dead”23 but secondary processing can also be found in Central Asia, North and South America, Melanesia, and Greece.24 While visiting the Torajans, an indigenous population in Indonesia that practices secondary processing, mortician Caitlin Doughty discusses how families care for the mummified bodies of their relatives, sometimes keeping them inside the home and referring to them as not dead, but merely sick until the final funeral rite is concluded.25 The different ontology of death present amongst the Torajans is visceral and embedded in daily life. It’s useful to expand the imaginary of how death can be understood—and though secondary processing may seem like an edge case, it also bears some connection to things like the Christian purgatory, an intermediary place the soul goes after death in order to undergo final purification, or embalming, common in North America as a way to extend the period before burial.26

Secondary processing is also reminiscent of the concept of “second loss,” coined by Debra Bassett, or “second death,” originating from Patrick Stokes. In a paper examining both, Rem Moore and Sarah Wambold describe,

A “second death’ is a social death that occurs when an individual’s name or memory is no longer known among the living. “Second loss,” however, acknowledges that “second death” has been complicated by the digital.27

Second death, ritual understandings of a liminal state between life and death, and changing medical and legal practices are all examples that de-center death from a fixed event that happens to a body (which cannot be decoupled from a person), into a social decision-making process where the ontology of what actually dies is flexible. They are also all extrinsic understandings of death.

From the perspective of the individual, death is sometimes a choice, as in suicide and euthanasia, but often otherwise. Death in a protocological context does not (and cannot) account for the personal, subjective experience of death. It is the perspective of the Turing interrogator, not the test subject. We cannot ask a protocol whether it feels sick, we can only observe it symptomatically.

Once we name death-as-a-decision, the lights come on and we see the puppet strings. Who has been given authority to decide that something is dead; what rituals or protocols are undertaken to cement its deadness? In the human context, doctors, lawyers, and sometimes religious figures play these roles. In the context of worlds like games or social media platforms, these roles are performed by a company or organization. In more decentralized worlds—protocols, fandoms, and the like—there may be no clear decisionmaker, introducing a fundamental anxiety.

As an example of a dead world that lacks a death-decider—there are plenty of dead blockchains. The particular nature of peer-to-peer protocols means the end state that gives the most clarity—all servers shut down—is very rarely reached. There is no decisionmaker who could turn off the protocol, and indeed no single server. This decentralization is the source of desirable properties, such as censorship resistance and ability to persist even in the face of takedown attempts by well-resourced actors. Nonetheless, some blockchains clearly die. In a report on the subject, Coinmarketcap suggests projects with negligible trading volume, joke projects, and projects with little to no funding are dead.28 Coinopsy maintains a list of dead coins, with clear criteria for being added to the list, including volume under 1,000 USD for three months, website offline, no trace of updates, and no nodes or other similar problems. As of June 2023, 2,439 coins are on its list, going back as far as 2011.29 99Bitcoins’ page for dead coins, formerly deadcoins.com, lists more than 1,700 blockchains that have died and for each one gives a series of “death indicators,” including: inactive Twitter, low volume, not indexed, not Listed on exchanges, and website down.30 Of these metrics, most are economic and others look at official communication output—but they are missing something central to worlding. Any sufficiently healthy world will spawn activity in peripheral forums where the protocol is discussed. It will spread and animate spaces outside itself. The life of the world is not only in the world. Looking for these spaces is an important and often overlooked world-assessment criteria.

One can imagine these initiatives to track dead coins as an emerging Order of Protocological Death,31 perhaps becoming an independent body the way the medical and legal profession become arbiters of human death. Such an organization could fill in as protocol death-deciders, for cases where no governance mechanisms exist or those mechanisms have failed—as well as maintain the lore of these dead worlds and facilitate the eulogies and funeral practices as appropriate. Already, the death indicators used by the deadcoin lists are like a doctor inspecting first for an absence of swallow reflex, then for no eye response to light, and no limb movement on painful stimulus. In Twice Dead, Lock writes,

Decentralists usually argue that because different parts of the body stop functioning and die at different times, death must be a process.32

The word “decentralists” here is interesting and perhaps significant.

Decentralized autonomous organizations, known as DAOs, are a hybrid between a decentralized world and a system that has an established decisionmaking process. Many DAOs die, as do all worlds—sometimes leveraging existing decisionmaking processes. DAO deaths should be the subject of further study, especially as cases where there are real stakes to the decision in the form of financial assets that should be redistributed to participants, spent, or otherwise handled.

A related case would be autonomous worlds, a framework for blockchain gaming proposed by 0xPARC. The way 0xPARC characterizes a world has much in common with the way we do here:

We inhabit Worlds—both physical and conceptual. We learn how to work and behave within them. We engage in tribalism, spatial reasoning, and territorialism, even within Worlds that live entirely in our minds. We have a sense for the boundaries of Worlds and their rulesets.33

Further, despite some worlds having physical artifacts,

the physical artifacts of such Worlds are not the reason that these Worlds are alive. Printing a million copies of a book doesn’t create a World, unless people read it, care about it, and inhabit it.34

But they go on to propose a quasi-immortality for blockchain-based worlds because their peer-to-peer substrate cannot be shut down. While the nature of the underlying technology does prevent premature death by shut down, much like printing a book doesn’t guarantee a world will grow, the continued ability to access an autonomous world doesn’t constitute life. These worlds will be as mortal as any other and their decentralization may eventually call for their own Order of Protocological Death.

Perhaps the worst case for a world is to linger indefinitely between life and death with no emerging death-decider. One of the important functions funeral rituals can serve is reconstituting society without the lost member35—the various social roles of the dead person must be taken over by others or changed. An incomplete funeral moment can impede the grief process. Turning again to an example from human death, Debra Bassett, a researcher who studies mortuary technology, recounts how,

a [research] participant named Pam told me how she has not upgraded her mobile phone for 5 years because of [. . .] treasured answer phone messages from her daughter, and although there are software packages available that would allow her to save the messages, she is too frightened to try them.36

Many similar examples highlight not only how contemporary social media selves can linger in a liminal state between life and death, but also the adjacent harms from the lack of a end state.

Another example of existential stress in the peer-to-peer context is what was named “the difficulty bomb” mechanism in Ethereum. Initially written into the protocol as part of the planned switch to proof of stake, the difficulty bomb was a feature where at a given point in time it would become exponentially more difficult to find correct blocks using the old proof of work mining system. Had the bomb been timed to go off before the functional PoS implementation had been created, the chain would have effectively been killed. As it became clear that shipping PoS would take longer than expected, the bomb had to be postponed—not once, but five times—and it came to have effects outside of those intended, such as making it more difficult for scam forks of ethereum to spring up. Though the change required to remove the bomb by a potential scammer was very small, it still created a sufficient barrier. It also became an opportunity to renegotiate mining rewards and other protocol updates. As Tim Beiko of the Ethereum Foundation explained:

People began to see the difficulty bomb as a way to renegotiate miner compensation, because if the miner’s don’t upgrade the software they’re going to be on a chain that doesn’t work. And then if all the users want the chain that has no difficulty bomb or delayed difficulty bomb and also lower issuance, then the miners are all going to have to switch.37

Further:

One time we pushed [the difficulty bomb] back for 18 months, and that was a terrible decision, because the fork [the technical name for a protocol update], literally took us 18 months . . . The opposite happened with EIP 1559, when we shipped [another fork]—we had the difficulty bomb happening and so we made the schedule fit that [in order] to not have to do two forks, like one to delay the bomb and then one with the actual feature.38

Now that Ethereum has transitioned to PoS, no equivalent mechanism to the difficulty bomb is planned. Instead the community debates protocol ossification, meaning whether current governance processes for protocol updates should wind down with an end state of no further changes. Proponents of ossification see it as important for resisting governance capture and maintaining the decentralization and resilience to threats that is often touted as one of blockchain’s core affordances.39

It is interesting to ask what role the forcing function of the difficulty bomb might have had on aligning economic incentives during an early phase of Ethereum’s growth, from 2015 to 2022. Could the requirements of the difficulty bomb have had the secondary effect of more robust governance or a reduced tendency towards ossification? What rate of updates leads to a greater long-term health of a protocol? All of these questions should be the subject of further research and the difficulty bomb is uniquely positioned as a case study: a recurring reminder of death in a living world.

An understanding of the mortality or ephemerality of data also allows attention to be directed to efforts at preservation, archiving, and memorialization. To think about death in a digital context is to consider the archive, the save file, the backup hard drive. A world that can’t die also can’t benefit from increased attention to these questions. Most of the worlds we have looked at here exist online—and it may be that the online context is uniquely suited to worlding. Certainly, starting a world online can be quicker than in physical space, since no offices, venues, or transit are needed. The digital context also lends itself to the question of archiving: everything is always already in a database. Naive reliance on the auto-save state, though, may paradoxically lead to worse memorial practices.

What kind of archive, cemetery, or memorial is appropriate for dead worlds? A first impulse might be to store all of the data that encompasses the world. In the game context, that would mean the game save file, the data of the map and all of its buildings. One could also store the game code, the game engine, even the operating system the game runs on. We could store every version of the world that exists, for every tick in game time, so that we could replay deterministically every move that every character made with every game item—in fact, in our attempt at constructing an archive for a digital world, we could reinvent a blockchain from first principles. But would we have captured what matters about the world?

In the Preserving Virtual Worlds Final Report, a product of collaborative research by Linden Lab, the creators of the online game Second Life, and several North American universities, the authors write:

An important part of the historical context for virtual world history is the fact that human beings (through their avatars) fill these digital environments with meaning that emerges from their activities in social spaces, regardless of whether the spaces are synthetic (digital) or physical.40

Furthermore,

If we save every bit of a virtual world, its software and the data associated with it and stored on its servers, it may still be the case that we have completely lost the history.41

The report calls this the fantasy of perfect capture: while we can back up the data that encompasses a game, this doesn’t capture what the game really is.42 A world, much like a protocol, does not exist in a static instant, in contrast to a standard, a blueprint, a single save file, or digital scan. A protocol must be enacted, and a world must be lived in.

The Github Arctic Code Vault epitomizes the fantasy of perfect capture. Part of the Github Archive Program, the vault is a data repository of some 21 terabytes of code, buried 250 meters underground in a decommissioned coal mine in the Arctic. Included was a snapshot of every Github repo with at least one star and any commits in the year preceding February 2, 2020.43 Unfortunately, the premise of storing this code in this way is unvalidated—even farcical. The point of git, the underlying tool that Github is an interface for, is to track changes to a codebase over time from many contributors—and yet the Code Vault has only a shallow copy. Who wrote this code and why? What did they use it for? What kind of people worked on it and what did they disagree about? It is a mistake to equate the meaning of this code with the code itself. Like the game save state in an MMO, something fundamental is absent about the life of an open source software project.

Indeed, the thing that dies is the thing that cannot be archived, and is the thing that the naive approach to storage encourages us to miss. It’s useful to contrast dumb storage with a memorial. With dumb storage, the fantasy of recreating the thing being archived can exist—and sometimes the thing itself or the original document. No such pretense persists with a memorial. Instead perhaps, a memorial exists as a testament to what cannot be archived. A memorial is a kind of compression technology: we make memorials when there is something uncapturable, too big, or that we want to stand in for a larger symbolic meaning.44

The Memorial against Fascism in Harburg is a useful example. Constructed in 1986 in a town near Hamburg, Germany, the monument is a 12-meter-high column on which the public was invited to make inscriptions:

From the day of the monument’s dedication on 10 October 1986 until 10 November 1993, the column was gradually lowered into the ground in eight stages. This created space for new comments, but it also symbolized the burial of memory. By the time the column disappeared into the ground, it had around 60,000 inscriptions of various types: signatures, contemplative reflections, anti-fascist quotes, proverbs and xenophobic slogans.45

An example of a very different but effective memorialization tactic is Empires of Eve by journalist Andrew Groen—a nonfiction book borne of deep immersion in the MMO EVE Online.46 While EVE is not dead, the book demonstrates an alternative approach to the preservation of an online world. Drawing from two years of research and interviews with 70 players, it chronicles the in-game events from 2003 to 2009: the changing alliances and cycles of war, as well as personal stories of key players.47 Much like other worlds, the meaningful life of the game is not in the game itself—one player with in-game name The Mittani who runs an alliance of 40,000 characters reveals:

“I never play Eve . . . I got bored of playing Eve by 2006.” Instead, what he plays is a game surrounding a game: a game of people, and a game that [CCP Games, developer of EVE Online,] doesn’t control. It’s a game played in “a zillion” chat rooms on Jabber, across multiple screens in his office, his spaceship bridge.48

While a game like EVE Online may make best sense remembered in a sprawling military history, no one right way to memorialize a dead world exists: much like Metcalf and Huntington conclude in Celebrations of Death, it is possible to undertake a “culturally nuanced account of emotion” in the context of a death ritual “only after the weight of providing a catch-all explanation has been lifted.”49 And indeed: “The diversity of cultural reaction is measure of the universal impact of death.”50

Importantly, death itself is not the enemy. Instead, it is when a protocol cannot be discarded or changed that it becomes more dangerous. Highly accurate autobiographical memory, or hyperthymesia—the inability to forget one’s past—is associated with negative effects, including depression and difficulty in personal relationships.51 Jill Price, one of the only 60 or so people who have been identified with the condition, characterized it as “non-stop, uncontrollable, and totally exhausting.”52 Permanence can also contain a threat as in the “хранить вечно” (keep forever) stamped by the KGB on the dossiers on its political prisoners53 or the converse wave of contemporary activism around the right to be forgotten.54 Forgetting—mortality, ephemerality, deletion—is what enables health, forgiveness, and grace.

If all media technology is an extension of the body, as has been often claimed,55 how can we characterize the ultimate endgame of technology? Is the maximally extended body immortal? In the age of ubiquitous digital content, dumb storage—naively saving the game world, branch HEAD, or blockchain state—is the default position.

The same is true of our personal data—we are all archives in search of an archivist. When Dropbox emails to say, “you’re running out of storage, upgrade now!” it is playing on your fear of death.56 A blockchain in particular makes a claim about time and permanence: that it is ongoing, that it is unidirectional, that the past is immutable, that it is singular. In most cases, this will turn out to be false. Not only are many chains dead, others have forked (time is not singular) or rewritten the past.

Does the archive only grow? In both a personal and cultural context, we are all amassing archives. By 2070, Facebook’s databases could contain more dead people than living ones.57 Even in 1945, Vannevar Bush, theorizer of the memex, complained that “publication has been extended far beyond our present ability to make real use of the record,”58 suggesting even then that making sense of the vast corpus of human knowledge was impossible. Now we exceed his wildest speculations with a glut of information. Consider the Internet Archive, an example from Bush brought to life: “[a] library of a million volumes could be compressed into one end of a desk”59 and one of the “[w]holly new forms of encyclopedias [that] will appear, ready-made with a mesh of associative trails running through them.”60 The Internet Archive’s About page makes explicit the proposition to grow without end:

Our mission is to provide Universal Access to All Knowledge.61

This mission is, of course, the source of its sacredness. If the archive of All Knowledge were ever to finish, what else then too must implicitly end? All blockchains have a similar fundamental assumption: the block height only ever increases and must increase. But we can ask also—from where will come the hard drives, server racks, “polyester film base coated with a gelatin layer of light-sensitive silver halides,”62 or compressed DNA storage?

This premise—the archive that only grows and its concurrent religiosity—is a specific sacredness related to a specific culture, one with a deep progress narrative and a growth-based economic system. Though sacredness, like memorials, often has to do with something “too big” or “too small” that cannot be articulated any other way, in an alternate world the act of deleting the archive could be as sacred as keeping it forever. What is the culture from which this different sacredness vector could originate?63

To look further at ephemerality in the context of the digital (and to move from the sacred to the profane), let’s turn to 4chan, a large online message board where the vast majority of posters are anonymous. Known for memes, trolling, and activism across a variety of political axes, 4chan is also a rare example of ephemerality of online content. A recent quantitative analysis of its popular discussion board known as /b/ describes the display and treatment of conversations:

Threads begin on page one and are pushed down as new threads are added. If a user replies to a thread, it is bumped back to the top of the first page. If the thread reaches the bottom of the fifteenth page, the thread is removed permanently and its URL returns a ‘Page Not Found’ error.64

The analysis found the median lifespan of a /b/ thread to be just 3.9 minutes.65 In this accelerated content environment, there are two mechanics for users to influence post lifespan: bump, which is commenting “bump” on a thread to push it to the top again, and sage (from the Japanese sageru, meaning “to lower”), which allows one to comment without bumping the thread. 2.16 and 0.77 percent of posts, respectively, were found to use these features. Further:

Though the site may be ephemeral, /b/ users have developed other mechanisms to keep valuable content. For example, users often refer to having a “/b/ folder” on their computers where they preserve images for future enjoyment or remixing. /b/ posters ask others to dig into their archives [ . . .]66

On 4chan, the foreknowledge of post deletion incentivizes both curation and archiving practices, both personal (a local /b/ folder) and collective (4chanarchive).

A related example is Orkut, a social media platform active from 2004 to 2014 and its largest user base in Brazil. In The Death and the Death of Orkut, Alice Noujaim looks at Orkut’s death process as it was administered by Google.67 When announcing the platform death, Google gave users two years to export their profile data, photos, and posts. At the same time, it announced the creation of a public archive of Orkut’s communities, shared boards with a huge variety of subjects. The creation of the community archive indicates,

Both Google and the user base understood that the most important thing about Orkut were not the individual profiles . . . but the collective spaces of interaction, the communities68

In other words, the communities are where the world of Orkut grew.

The personal data users could download from Orkut echoes the local /b/ folder—lacking a central narrative or single storage location. The community archive mirrors the 4chanarchive. Unexpectedly though, in 2017, Google announced the Orkut archive too would be shut down, giving users just two weeks’ notice and no clear backup procedure. Noujaim recounts:

The distinction was interesting: while three years earlier Google had stated the Community Archive was for ‘eternity’ whilst executing a careful protocol of deactivation of a living thing, the memorial of that thing was given a rushed ending.69

Tomas Zahora, in “The Art of Forgetting the Middle Ages,” discusses Agrippa and the medieval technology of memory—a series of tactics for increasing the human capacity to remember.70 These tactics sometimes involved the construction of a memory palace, an imagined setting in which the memories could be placed spatially, best accompanied by emotionally evocative or familiar imagery.71

Alongside this art of increasing memory was a less-discussed art of forgetting, undertaken when memory palaces had outgrown their usefulness and how “a culture dependent on complex mnemonic systems handled an excess of remembered material.”72 Techniques can be as literal as visualizing a wing of the memory palace being destroyed or “crowding” where:

[t]oo many images overlapping one another in a given location, images that are too much alike, will confuse and even cancel one another out.73

These early approaches to forgetting align with contemporary findings about memory: in particular how post-event information can modulate memory, impair recall, or create:

. . . a memory of an event that never took place or of a detail that was never part of the original information.74

“Substitution” is a contemporary tactic in post-event information that mirrors crowding. For example, after watching a video clip with a stop sign, if researchers ask participants about a different kind of street sign, participants show confusion about what sign was seen.75 Zahora considers that the art of forgetting may have become particularly urgent in the era of Agrippa’s writing, year 1662, because it was a time of profound cultural change. He writes,

Does it mean that in times of paradigmatic change our minds are stuck with outdated mnemonic frameworks amassed during years of study and subsequent practice? What happens when a whole mode of learning shows signs of stress?76

No universal understanding of what constitutes a good death (or when forgetting is appropriate) exists, for protocol nor human, yet perhaps a few examples will be helpful. In terms of worlds, we can recall the contrasts of the death of Orkut to the death of its Community Archive: the former planned with clear process, the latter rushed and sudden. As Noujaim writes, “Orkut had a good death, its archive had a bad one.”77

Memorial practices can be part of a good death: Seth Killian, who was part of a small team working on a video game which was suddenly shut down despite a thriving player community, describes the experience as a “bad death” which

mostly came from inability to revisit even a kind of memorial. Instead there was kind of . . . nothing.78

For the team, releasing a free version of the game two years later that others could build on allowed the feeling of the game being “returned to the ecosystem”79 to change their relationship to the events.

Looking at good death in the human context, a meta-analysis of 36 papers providing attempts to define a good death found that preferences about the dying process was the most frequent theme, including:

the death scene (how, who, where, and when), dying during sleep, and preparation for death (e.g., advance directives, funeral arrangements).80

A working group on the care of older people proposed twelve principles of a good death in their final report. Starting with “To know when death is coming, and to understand what can be expected,” the list closes with “To be able to leave when it is time to go, and not to have life prolonged pointlessly.”81

Protocol makers, know this: your protocol will die. It may become so inflexible that it must be discarded —“if the constitution is too rigid, it becomes necessary to kill the king”82—or the conditions around it may change so much as to become unrecognizable. Of the many possible protocological deaths (and a starting taxonomy can be found in “Founding Memorabilia from the Order of Protocological Death,” the artifact that accompanies this paper83), ask: What constitutes the life of your protocol? What symptoms or death indicators could be used to assess its health? These indicators may not reside in the protocol itself—indeed, the more alive the protocol is, the more likely they are to have spread elsewhere. Identify the decisionmaking processes that exist in relationship to your protocol and whether they would withstand an existential question.

A decision-making process can be assessed by whether it is sufficiently robust that the “losers” of any governance outcome retain faith in the decision-making process itself. The death decision may be the ultimate challenge. In “Killswitch Protocols,” Eric Alston, Garrette David, and Seth Killian examine the affordances of different decision-making processes as they relate to killswitches, failsafes, and overrides—all of which uniquely reify the death-decision.84 They discuss how killswitches can reveal structures of authority and perhaps even become adversarial vectors, warning, “who controls the killswitch also controls the system’s survival.”85

The death decision poses a related set of questions—if an Order of Protocological Death were ever broadly established, care will need to be taken that it has balanced incentives. Norms may also be established for protocol euthanasia, as in the DAO death: what kinds of participant support are required for such a death to be legitimate?

Finally, what ritual acts or archive practices will render legible the meaning of the protocol to the future? From the local /b/ folder, to Empires of Eve, to the game eulogy, to the burning wing of a memory palace—a memorial practice should be specific to the protocol and world that grew around it. Duplicating and storing the content of a world, especially at just one point in time, is insufficient. You will miss the world for the map.

Knowledge of mortality allows the writing of history. In The Storyteller, Walter Benjamin reminds us of the narratological importance of the ending:

[i]t is, however, characteristic that not only a man’s knowledge or wisdom, but above all his real life . . . first assume transmissible form at the moment of his death.86

And also,

Death is the sanction of everything that the story-teller can tell. He has borrowed his authority from death.87

Let us use that authority now on this essay itself. It lived like a climbing vine, meandering and full of details. May it die like a dandelion, scattering seeds on the wind. Δ

Sarah Friend is an artist and software developer currently based in Berlin, Germany. She was formerly the smart contract lead for Circles UBI, a community currency that aims to create a more equal distribution of wealth, as well as for Culturestake, a quadratic voting project targeting arts funding. In 2022, she was a visiting professor at The Cooper Union. Recent solo exhibitions include Off: Endgame at Public Works Administration, New York, and Terraforming at Galerie Nagel Draxler in Berlin. isthisa.com

-

1. UnoriginalAnomalies, “When is an MMO considered ‘dead’ to you?” Reddit, December 21, 2022. www.reddit.com/r/MMORPG/comments/zrw3u2/when_is_an_mmo_considered_dead_to_you/

-

2. “What constitutes a ‘dead MMO’?” (discussion), Reddit, January 2, 2015. www.reddit.com/r/MMORPG/comments/2r5ad1/discussion_what_constitutes_a_dead_mmo/

-

3. tanstaafI, “The Signs: How do you know if an MMO is dying?” Reddit, October 26, 2014. www.reddit.com/r/MMORPG/comments/2kdlty/the_signs_how_do_you_know_if_an_mmo_is_dying/

-

4. Ian Cheng, “Worlding Raga: 2—What Is a World?” Ribbonfarm (blog), March 5, 2019. www.ribbonfarm.com/2019/03/05/worlding-raga-2-what-is-a-world/

-

5. degtiar, “EA-Land: The Final Countdown,” How They Got Game Project, Stanford University, 2008. archive.org/details/EALand_FinalCountdown

-

6. Jon Fingas, “Online RPG ‘Asheron’s Call’ to shut down after 17 years,” Engadget, December 21, 2016. www.engadget.com/2016-12-21-asherons-call-to-shut-down.html

-

7. PC Gamer, “The last moments of Asheron’s Call” (video), January 31, 2017. www.youtube.com/watch?v=o77BL-hCHxA

-

8. Margery Williams, The Velveteen Rabbit (London: Egmont Books, 2004).

-

9. Ruben Alexander, “The First Blockchain Wedding,” Bitcoin Magazine, October 5, 2014. bitcoinmagazine.com/culture/first-blockchain-wedding-1411842604

-

10. Ivan Dikalenko, “Len Sassaman: A Cypherpunk, Scientist, and Cryptographer Immortalized in Bitcoin,” Gagarin.news, February 9, 2023. gagarin.news/news/len-sassaman-the-man-memorialized-in-blockchain/

-

11. Terra Nullius, “In memory of Nóirín Plunkett, passed away July 28th, 2015,” Opensea, August 7, 2015. opensea.io/assets/ethereum/ 0x3a921bf2c96cb60d49aff09110a9f836c295713a/6

“Nóirín Plunkett,” Geek Feminism Wiki, Fandom (website), 2015. geekfeminism.fandom.com/wiki/N%C3%B3ir%C3%ADn_Plunkett -

12. Bo Zhao and Xu Huang, “Encrypted monument: The birth of crypto place on the blockchain,” Geoforum 116 (2020): 149–52. doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.08.011

-

13. Margaret M. Lock, Twice Dead: Organ Transplants and the Reinvention of Death (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001).

-

14. William Tebb and Edward Perry Vollum, Premature Burial, and How It May Be Prevented, 2nd edition, ed. Walter R. Hadwen (London: Swan Sonnenschein, 1905). dn790002.ca.archive.org/0/items/prematureburialh00tebbuoft/prematureburialh00tebbuoft.pdf

-

15. Lock, p. 8.

-

16. Lock, p. 38.

-

17. Wikipedia, “International Organ Donor Rates,” accessed May 20, 2020. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_organ_donor_rates

-

18. Robert M. Jarvis and Megan F. Chaney, “‘The Living, the Dead, the Undecided’: An Annotated Bibliography of Law Review Articles Dealing with the Law of Absentees and Returnees,” International Journal of Legal Information 44, no. 2 (2016): 178–207.

doi.org/10.1017/jli.2016.22 -

19. Peter Metcalf and Richard Huntington, Celebrations of Death: The Anthropology of Mortuary Ritual (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).

-

20. Arnold Van Gennep, The Rites of Passage: A Classic Study of Cultural Celebrations, trans. Monika B. Vizedom, and Gabrielle L. Caffee (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960).

-

21. Metcalf and Huntington, p. 32.

-

22. Metcalf and Huntington, p. 85.

-

23. Metcalf and Huntington, p. 33.

-

24. Metcalf and Huntington, pp. 34–35.

-

25. Caitlin Doughty and Landis Blair, From Here to Eternity: Traveling the World to Find the Good Death (New York: W.W. Norton, 2017), pp. 33–51.

-

26. Metcalf and Huntington, p. 197

-

27. Sarah Wambold and Rem Moore, “Only Loss,” Do Not Research, July 20, 2023. donotresearch.substack.com/p/sarah-wambold-and-rem-moore-only

-

28. Werner Vermaak, “What Are Dead Coins?” CoinMarketCap, 2021. coinmarketcap.com/alexandria/article/what-are-dead-coins

-

29. Coinopsy, “List of Dead Coins,” n.d., accessed August 31, 2023. www.coinopsy.com/dead-coins/

-

30. 99 Bitcoins, “Dead Coins—1600+ Cryptocurrencies Forgotten by This World,” January 3, 2023.

99bitcoins.com/deadcoins/ -

31. Echoing the Order of the Good Death, a death acceptance organization founded in 2011. Wikipedia, “The Order of the Good Death.” en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Order_of_the_Good_Death

-

32. Lock, p. 73.

-

33. ludens, “0xPARC,” 0xparc.org, accessed August 31, 2023. 0xparc.org/blog/autonomous-worlds

-

34. ludens.

-

35. Metcalf and Huntington, p. 84.

-

36. Debra J. Bassett, “The Digital Afterlife from Social Media Platforms to Thanabots and Beyond,” in Death and Anti-Death: Two Hundred Years after Frankenstein, ed. Charles Tandy, vol. 16 (Ann Arbor: Ria University Press, 2018). www.researchgate.net/profile/Debra-Bassett-2/publication/327955255_Digital_Afterlives_From_Social_Media_Platforms_to_Thanabots_and_BeyondForthcoming/links/5c3457f9299bf12be3b6879c/Digital-Afterlives-From-Social-Media-Platforms-to-Thanabots-and-BeyondForthcoming.pdf

-

37. Tim Beiko, interview, 2023.

-

38. Beiko.

-

39. Micah Zoltu, interview, 2023.

-

40. Jerome Mcdonough, Robert Olendorf, Matthew Kirschenbaum, et al., Preserving Virtual Worlds Final Report (National Digital Information Infrastructure and Preservation Program, Library of Congress, 2010). hdl.handle.net/2142/17097

-

41. Mcdonough et al., p. 38.

-

42. Mcdonough et al., p. 37.

-

43. GitHub Archive Program, “Arctic Code Vault,” accessed August 31, 2023. archiveprogram.github.com/arctic-vault/

-

44. Kara Kittel and Toby Shorin, in conversation.

-

45. Memorials in Hamburg in Rememberance of Nazi Crimes, “Memorial against Fascism in Harburg,” accessed August 31, 2023. gedenkstaetten-in-hamburg.de/en/memorials/show/harburger-mahnmal-gegen-faschismus-1

-

46. Andrew Groen, Empires of EVE: A History of the Great Wars of EVE Online (Andrew Groen, 2016).

-

47. Robinson Meyer, “The First History of Video Game Warfare,” The Atlantic, April 6, 2016. www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2016/04/how-to-write-a-history-of-a-video-game-war/476964/

-

48. Robert Purchese, “Inside Eve Online’s Game of Thrones,” Eurogamer.net, March 29, 2015. www.eurogamer.net/inside-eve-onlines-game-of-thrones

-

49. Metcalf and Huntington, p. 2.

-

50. Metcalf and Huntington, p. 24.

-

51. Alix Spiegel, “When Memories Never Fade, the Past Can Poison the Present,” National Public Radio, December 27, 2013. www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2013/12/18/255285479/when-memories-never-fade-the-past-can-poison-the-present

-

52. Amanda Macmillan, “The Downside of Having an Almost Perfect Memory,” Time, December 8, 2017. time.com/5045521/highly-superior-autobiographical-memory-hsam/

-

53. Viktor Mayer-Schönberger, “Useful Void: The Art of Forgetting in the Age of Ubiquitous Computing,” KSG Faculty Research Working Paper Series RWP07-022, 2007. dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.976541

-

54. Wikipedia, “Right to Be Forgotten.” en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Right_to_be_forgotten

-

55. As in Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (Berkeley, Calif.: Gingko Press, 1964).

-

56. Beth Mccarthy, in conversation.

-

57. Carl J. Öhman and David Watson, “Are the Dead Taking over Facebook? A Big Data Approach to the Future of Death Online,” Big Data & Society 6, no. 1 (2019). doi.org/10.1177/2053951719842540

-

58. Vannevar, Bush, “As We May Think,” The Atlantic (July 1945), pp. 101-108. www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1945/07/as-we-may-think/303881/

-

59. Bush, p. 102.

-

60. Bush, p. 103.

-

61. Internet Archive, “Internet Archive: About IA,” 2009. archive.org/about/

-

62. This film is the material used in the Github Arctic Code Vault. Jędrzej Sabliński and Alfredo Trujillo, “Piql. Long-Term Preservation Technology Study,” Archeion 122 (2021): 13–32. doi.org/10.4467/26581264arc.21.011.14491

-

63. Arkadiy Kukarkin asked the question, “Is sacredness a vector or a scalar?” in conversation.

-

64. Michael Bernstein, Andrés Monroy-Hernández, Drew Harry, et al., “4chan and /b/: An Analysis of Anonymity and Ephemerality in a Large Online Community,” Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media 5, no. 1 (2021): 50–57. doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v5i1.14134

-

65. Bernstein et al., p. 53.

-

66. Bernstein et al., p. 54.

-

67. Alice Noujaim, “Death and the Death of Orkut,” Summer of Protocols (2023). summerofprotocols.com/research/death-and-the-death-of-orkut

-

68. Noujaim.

-

69. Noujaim.

-

70. Tomas Zahora, “The Art of Forgetting the Middle Ages: Cornelius Agrippa’s Rhetoric of Extinction,” The Sixteenth Century Journal, 46 no. 2 (2015): 359–80. www.jstor.org/stable/43921245

-

71. For an extended discussion of memory protocols, see also Kei Kreutler, “Artificial Memory and Orienting Infinity,” Summer of Protocols (2023). summerofprotocols.com/research/artificial-memory-and-orienting-infinity

-

72. Zahora, p. 362.

-

73. Mary J. Carruthers, The Craft of Thought: Meditation, Rhetoric, and the Making of Images, 400–1200 (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2000), p. 55.

-

74. Ruth Mayo, Yaacov Schul, and Meytal Rosenthal, “If You Negate, You May Forget: Negated Repetitions Impair Memory Compared With Affirmative Repetitions,” Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 143, no. 4 (2014), 1541.

-

75. Mayo et al., p. 1542.

-

76. Zahora, p. 359.

-

77. Noujaim, “Death and the Death of Orkut.”

-

78. Seth Killian, interview, 2023.

-

79. Killian, 2023.

-

80. Emily A. Meier, Jarred V. Gallegos, Lori P. Montross Thomas, et al., “Defining a Good Death (Successful Dying): Literature Review and a Call for Research and Public Dialogue.” The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 24, no. 4 (2016): 265. doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2016.01.135

-

81. Debate of the Age Health and Care Study Group, “The Future of Health and Care of Older People: The Best is Yet to Come” (London: Age Concern, 1999), cited in Richard Smith, “A Good Death: An Important Aim for Health Services,” BMJ 320 (2000): 129.

doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7228.129 -

82. Tim Beiko, in conversation.

-

83. Sarah Friend, “Founding Memorabilia from the Order of Protocological Death,” Summer of Protocols, 2023. summerofprotocols.com/research/good-death

-

84. Eric Alston, David Garrette, and Seth Killian, “Killswitch Protocols.” Summer of Protocols, 2023. summerofprotocols.com/research/killswitch-protocols

-

85. Alston et al., “Killswitch Protocols.”

-

86. Walter Benjamin, “The Storyteller: Reflections on the Works of Nicolai Leskov,” trans. Harry Zohn, Chicago Review 16, no. 1 (1963): 89. doi.org/10.2307/25293714

-

87. Benjamin, p. 89.

© 2023 Ethereum Foundation. All contributions are the property of their respective authors and are used by Ethereum Foundation under license.

All contributions are licensed by their respective authors under CC BY-NC 4.0.

After 2026-12-13, all contributions will be licensed by their respective authors under CC BY 4.0. Learn more at: summerofprotocols.com/ccplus-license-2023

Summer of Protocols :: summerofprotocols.com

ISBN-13: 978-1-962872-22-5 print

ISBN-13: 978-1-962872-48-5 epub

Printed in the United States of America

Printing history: July 2024

Inquiries :: hello@summerofprotocols.com

Cover illustration by Midjourney :: prompt engineering by Josh Davis

«abstract composition where solid geometric forms are gradually being enveloped and erased by an expanding black void, exploded technical diagram»