Welcome to the Swarm

Rafael Fernández

ON the internet, we are part of swarms: networks of people, bots, and content, coordinated through algorithmic feedback loops. Swarms are harbingers of misinformation, heralds of mutual aid, and representatives of the public will. But this is not our grandparents’ crowd. Swarms are networked tempests of humans and information. Most importantly, they can act collectively without explicit protocols; they are minimally protocolized entities.

In this research, I document a variety of swarms, such as the mutual-aid response to the devastation of Hurricane María, to uncover their unique methods of cooperation. To understand swarms, we also need to understand their peers within the broader category of online formations. This category includes group entities like memetic tribes and online communities that have explicit protocols which separate them from their swarm peers and makes them more explicitly manageable. This inevitably leads us to the question: How do we steer swarms?

Algorithmic Coordination

The sky turned lilac at the break of dawn on September 22, 2017. It was an omen of Juracán, the wind spirit, summoned by the indigenous deity Guabancex. Hurricane María, the worst storm since 1899, was about to make landfall in Puerto Rico. It was mythic: the storm crossing on to land one minute after sunrise. Thousands would die in the aftermath.1 Millions of Puerto Ricans living in the U.S. and around the world waited in anticipation, without a way to connect to or help their family and friends.2

A Berlin-based Puerto Rican working in climate venture-building, Jorge Vega Matos fidgeted on his phone through the morning, watching his Facebook feed nervously. He dreaded the challenges his elderly parents and family might face in the coming days and weeks. Unknown to Jorge, an old acquaintance and Puerto Rican social activist in New York named Pablo Benson did the same.3

There was a deafening silence online. Everyone was alone but watching together As the silence continued due to an island-wide blackout, Jorge noticed that the Puerto Rican diaspora had begun to share drop-off points on Facebook for aid supplies. Rumors of stronger-than-expected damage crawled from phone to phone, urging those with an internet connection to broadcast their fears and take action. Facebook’s ever-watching algorithm understood the opportunity for engagement and amplified their voices.

A collective direction emerged as anxiety transformed into support:

Let’s not delay, let’s get supplies to those in need.

There was no banner or organizing institution, just posts about where to go and visual memes with lists of useful supplies. Jorge’s feed became a cacophony of activity. The digital diaspora had mobilized into a swarm: a network of people, content, and bots kept aligned by the algorithms of Facebook’s feed. It was a symbiotic alliance between social media and the Puerto Rican community: both needed to aggregate attention.

By the end of the day in Berlin, while Hurricane María was still ravaging the island, Jorge had created a public spreadsheet to aggregate supply drop-off points circulating on Facebook.4 He shared the link with various mutual aid groups, in hopes of accelerating donations. In New York, Pablo saw the spreadsheet and immediately forwarded it to others in his network. It turned out that the recipe for their swarm-like collaboration had been simple: provide a platform of connection to those with a common desire. The message found its way across the Atlantic:

We’re creating a team and we want to use your spreadsheet.

It was not the presence of certain protocols5 but their absence that gave the swarm its advantage. While government agencies and aid organizations sought approvals, individuals were able to act freely and broadcast their intentions via posts. Social media had enabled collaboration at scale through algorithms and instant messaging rather than being slowed down by explicit protocols,6 central planning, or strategic oversight.

Swarm Sighting

The story of Hurricane María highlights the structures and affordances of online swarms. But swarms are all around us. Other instances are regularly referenced in pop culture and daily news: celebrity cancellation raids, misinformation campaigns, fandom hypes, activist rallies, and memestock frenzies.

We can see another swarm’s footprint in the paths to ruin of four banks in 2023. The episode began that year when the Silicon Valley Bank published a surprise announcement on Wednesday, March 8. In it, the bank mentioned that it was taking action to address some liquidity challenges. A frenzy of panicked founders and CEOs (sparked in part by newsletter writer Byrne Hobert’s analysis of the situation7) messaged each other frantically as funds (such as Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund) advised them to withdraw their money. A torrent of provocative content flooded digital spaces. The swarm had been summoned.8

Screenshots of texts and emails were forwarded from one person to another. Posts on social media and in group chats created a pattern. In turn, the algorithms identified it as highly engaging content and accelerated its reach. The impending collapse manifested itself: within a day, over $42 billion had been withdrawn. The bank was unable to react in time. By March 10, just two days later, the bank was placed under the receivership of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC).9 Later, it became evident that the banking collapse was incited by other issues, but the swarm had accelerated its fate, striking like lightning fueled by desperate attention. Three more banks were claimed throughout the summer. Eventually, attention moved elsewhere and the swarm dissipated.

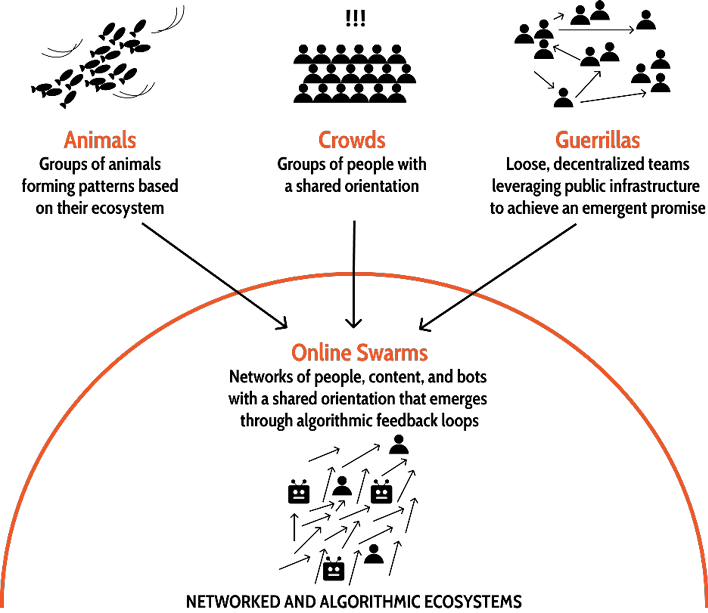

The hurricane response and the bank run are examples of online swarms: networks of people, content, and bots. They allow participants to act individually, with collective impact. Through a shared orientation10 that emerges in algorithmic feedback loops, swarms coordinate without internally directed protocols.11

Animals, Crowds, and Guerrillas

Swarms mirror similar patterns we see in animals, crowds, and guerrillas. Animal aggregations such as fish shoals12 evade danger by finding dark waters. Army ants build bridges over tricky terrain.13

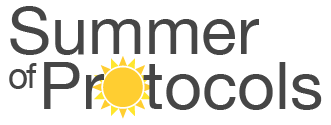

Figure 1. Online swarms exist within networked and algorithmic ecosystems. Swarms are similar but distinct to other collective groups that rely on emergence: animal aggregations, crowds, and guerrillas.

Online swarms also create collective solutions, but navigate networked online worlds instead of purely physical ones. The hurricane response built bridges of information enabling a supply chain of aid. The bank runs evaded financial ruin by collectively removing themselves from the unsafe institutions. Yet unlike animal aggregations, online swarms include a diversity of agents—people, content, bots, and algorithms—each with their own objectives or programming.

It is not sufficient to characterize swarms as a basic mixed crowd. In a crowd, participants gather organically and then act as a collective.14 We can picture a crowd of people gathering at a sunny spot in the park. Each person makes an individual decision to join and move from one part of the park to another. From afar, it would seem as though the crowd was working together. In reality, the sun was serving as a shepherd. For an online swarm, the sun is the algorithm.

But swarms operate with key differences. They include spectral objects like bots and content. They are digital-first, while crowds are often physical gatherings: location and mobilization are decoupled in a swarm. Additionally, swarms are deeply networked and everyone can broadcast information or send instant messages to each other. In contrast, crowd participants only communicate with their nearest physical neighbors.

At the intersection of algorithmic navigation and networked crowds, swarms take on guerrilla-like traits. They use their ecosystem as infrastructure for communication and coordination. They also form cell-like teams. These teams are autonomous and self-contained, each with its preferred protocols, but globally oriented via an emergent promise.

Like guerrillas, the Hurricane María response swarm relied on broadcasting to disseminate tactics; it had cell-like teams, each with its own protocols. Within their respective digital localities, Jorge and Pablo coordinated to apply their own protocols. They published updates in a dedicated Facebook group and hosted daily video calls, making use of experiences they’d had with Occupy Sandy mutual aid efforts in 2012. In tandem, Jorge and Pablo monitored the information and distribution, adjusting plans as needed. When they heard that the local government was being ineffective with supply distribution, they promoted a message through direct calls and group updates:

Channel the supply aid directly to local centers.

Jorge and Pablo were well-attuned to the changing environment.15 Fortunately, Facebook’s algorithms did not intervene negatively during the initial mobilization.

Coordination across swarm participants is organic, but not trivial. Without a central plan or governance team, Jorge, Pablo, and others like them oriented themselves around a promise that emerged from social media conversations:

Get supplies to those in need.

In the words of John Robb, researcher of modern guerrilla warfare:

This promise is the central connection between all the members in the [guerilla] community. Each member can have specific motivations that are substantially different from any of the others. In the case of warfare, these alternative motivations can be patriotism, hatred of occupation, ethnic bigotry, religious fervor, tribal loyalty, or what have you. It doesn’t matter as long as they agree with the plausible promise.16

Promises are not like business missions or goals. Promises have no associated metrics or objectives, only an associated orientation, defined by Kei Kruetler as

situational awareness that arranges knowledge in a selective and associative manner aligned with a particular purpose.17

Additionally, promises are not necessarily quantifiable, objective, or even rational.18 While a goal may be “build a boat” or “learn to fish,” a promise would be “help us learn to yearn for the sea.”19 Participants contribute to the promise in harmony, without formulating a global plan. Their actions are broadcast, forming a virtuous feedback loop that strengthens the swarm’s orientation.

The Silicon Valley Bank collapse didn’t have a collective objective or a project management structure. Instead, it oriented people’s actions around another promise:

The bank will collapse, act now to save your business.

Panicked business leaders took individual action and told their peers to do the same. They were united, but not unionized.

Figure 2. Swarm participants take action toward an emergent promise

But while swarms have some guerilla-like traits, they are not exactly like guerrilla groups. Jorge and Pablo were part of a much larger network of social media posts and relied on algorithmic feedback loops for coordination. Their swarm would have dissipated if attention had waned or Facebook had removed their ability to communicate. The swarm’s network of people, content, and bots was oriented20 towards the promise; but that does not mean they had the same orientation, only a sufficient overlap. After all, yearning for the sea is a personal calling, interpreted by each of us differently. In summary, swarms are networks of people, content, and bots with shared orientations that are strengthened by their ecosystems’ algorithmic feedback loops.

Swarms have a diverse set of participants who constantly broadcast their actions, algorithms that support their growth, and an emergent promise that harmonizes intentions. At the same time, their participants have individual agency, do not adhere to a collective “we,” and are constrained by their host platforms instead of internal protocols. Distinct from animal aggregations, crowds, and guerrilla groups, online swarms are a ubiquitous digital phenomenon.

It’s worth noting that swarm-like formations, which we might call proto-swarms, predate the internet. Their coordination tactics and consequences appear in all highly networked environments. Brown University economist Peter Garber tells an eerily swarm-like story regarding the phenomena of tulip mania. Tulip mania was a period in the Dutch Golden Age, in the seventeenth century, during which contract prices for fashionable tulip bulbs reached extraordinarily high levels, and then collapsed. Garber says:

These [tulip] markets consisted of a collection of people without equity making an ever-increasing number of “million-dollar bets” with one another with some knowledge that the state would not enforce the contracts. This was no more than a meaningless winter drinking game, played by a plague-ridden population that made use of the vibrant tulip market.21

Tulip mania had direct parallels to modern-day swarms: it was a network of people (traders) and content (contracts) with a similar orientation (speculation), guided by an algorithm (the tulip market).

Stories like these showcase proto-swarms. They may have not inhabited the internet world, but they were supported by tight communication feedback loops within a networked environment. Like today’s swarms of degens on WallStreetBets, these old-school traders created an accelerating cycle of speculation. Further research on religious revivals, mass manias, and events like the U.S. gold rush might help us find other proto-swarms across history.

Life in the Swarm

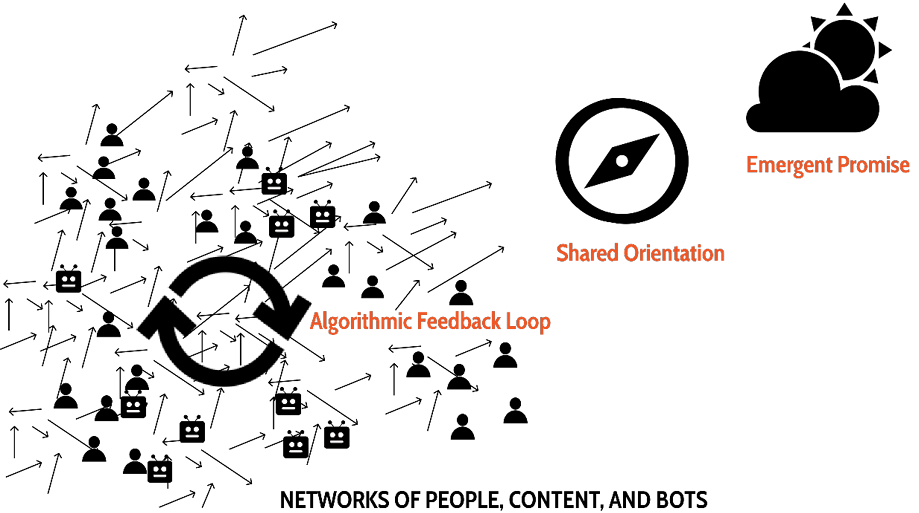

Swarms, like hurricanes, are gargantuan tempests with a predictable life cycle. They are fueled by natural feedback loops in their ecosystem. The feedback loop for hurricanes is between warm ocean waters and moving air. For swarms, eager algorithms amplify our actions to increase engagement, forming a feedback loop.

Also like hurricanes, swarms don’t have an absolute beginning or end. They emerge, never quite not there. Before a hurricane there’s a tropical storm and before that, a tropical depression of wind and rain. And just as they emerge, they dissipate.22 When a hurricane hits land, the feedback loops are interrupted and the strength of the winds wanes. Hurricanes essentially fade away. Swarms follow a similar path.

Figure 3. Online swarm lifecycle. Three main phases: emergence, acceleration, and dissipation. During each phase, the online swarm is powered by the web of algorithms in its ecosystem.

Prior to Hurricane María, Jorge and Pablo’s Facebook feeds were already filled with the diaspora network, their posts, and latent energy. Hurricane María presented an anchoring event that served as an orientation catalyst. The ocean-like currents of social media had reached the right temperature, strengthening the swarm’s feedback loop of attention. As a result, the mutual-aid swarm materialized as the diaspora aligned its orientation towards an emergent promise.

The strength of the feedback loop of the mutual-aid swarm is illustrated by Jorge’s database and the resulting supply chain. Hundreds of people across the globe began donating their time and aid supplies, following instructions found in visual memes on whichever social media service they were using. The content drew in spectators and transformed them into volunteers.

Supplies were gathered together at the drop-off locations and often brought as checked baggage on commercial flights to skirt established assistance protocols. As the scale of donations increased, volunteers prepared pallets and sent them via air and ocean freight. Within weeks, to ensure the supplies were not being stolen (or confiscated by government officials), donors were chartering private flights, accompanied by volunteers who hand-delivered donations to locations around Puerto Rico. Jorge recounted the following year:

I experienced this hive mobilization first-hand: The day after the hurricane, I started collating all the information I found about donation drop-off points, and overnight contributors from Seattle to Atlanta started pitching in. . . . Together, we built one of the most complete databases of its kind in the US within a week.23

But compounding growth is not sustainable. Like hurricanes, swarms only grow as long as the ecosystem supports their presence. Even if a hurricane doesn’t hit a landmass or move to cooler waters, its mechanisms are self-limiting: hurricane winds cool the warm water required for their formation.24 A swarm’s life cycle ends in a similar fashion. Swarms dissipate as soon as their source of attention is consumed or interrupted which can be due to achieving the promise or when a platform’s algorithm shifts focus. Swarms are dependent on the ecosystem they inhabit.

When Jorge went to Puerto Rico a few weeks after landfall, he was amazed. The local aid centers were fully staffed and didn’t have the need or time for new volunteers. The swarm’s promise had been achieved. New communities of support solidified and attention shifted from Facebook messages to government aid programs and local support networks. Facebook and other social media, in turn, sought new sources of engagement. Soon after, the working group between Pablo and Jorge disbanded. Yet the data representing their posts and replies persists, shaping future experiences across social media. The algorithms will surely try to mobilize the dormant swarm when the virtual waters warm once again.

Swarm Experiences

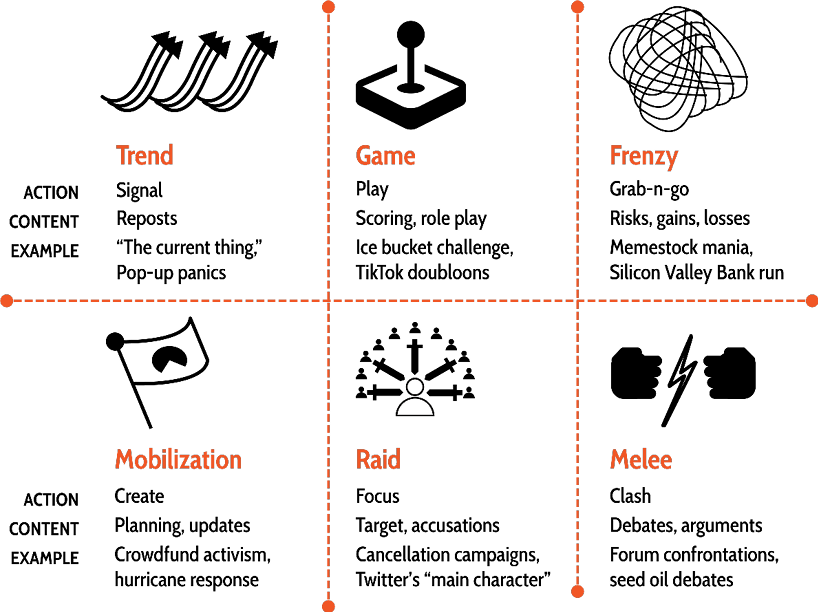

Swarms can vary widely in their impact and the emotions they evoke. The collective behavior of participants creates distinct experiences. In the case of the Hurricane María response, the emotional reaction was urgent and inspirational. In contrast, the Silicon Valley Bank run fuelled anxiety. Other swarms can seem playful, focused, or exciting. In my research, six common swarm experiences emerged (see figure).25 Each of the experiences is defined by the swarm’s actions. For instance, during the hurricane mobilization, people created a supply chain of mutual aid. On the other hand, during the bank run frenzy, people acted in a grab-and-go manner, moving with haste to secure their assets.

Figure 4. Six common swarm experiences in contemporary social media

Other kinds of swarm experiences include trends, games, raids, and melees. Trends involve widespread signaling, as seen with trending hashtags or “the current thing.”26 Games are characterized by playful interactions, like sharing contrasting photos to show fitness progress. Raids are adversarial; they involve focusing on a target such as a distressed celebrity. Melees consist of large-scale clashes on topics like health and diet, often taking place in public forums.

An example of a game-centered swarm appeared in 2022. An unknown number of participants on TikTok, likely in the millions, started playing a game to collect imaginary coins called doubloons.27 Anyone could decide to participate in the game.28 As social media users browsed videos on their feeds, they would encounter videos with instructions to add or remove doubloons from their inventory. Some even offered virtual and imaginary items, like a boat or a house, in exchange for doubloons. Each participant made up their own hyper-local rules, based on their interpretation and experience.

Curiously, there was no accompanying software application. Participants kept track of their coins on their phones. Then, they created videos that others might encounter. The game lasted a few months, with various “rules” emerging to manage the supposed inflation problem.29

While many swarms exhibit benign, playful, or creative behaviors, others are summoned with the explicit intent to cause harm. Instances of state-sponsored interference in elections have been well-documented. For example, The Guardian reported that an individual named Hanan offered “black ops” services:

Hanan told the undercover reporters that his services [. . .] were available to intelligence agencies, political campaigns and private companies that wanted to secretly manipulate public opinion. He said they had been used across Africa, South and Central America, the US and Europe. One of [the team’s] key services is a sophisticated software package, Advanced Impact Media Solutions, or Aims. It controls a vast army of thousands of fake social media profiles [. . .]30

In the future, other examples are sure to emerge, especially as bots and autonomous content31 become more common. In particular, swarms may become people-less, composed entirely of digital objects and media. As Byung Chul Han observed:

Physical objects, which used to be mute, are now starting to talk.32

An early example of a people-less swarm happened on May 9, 2010, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average dropped over 1,000 points, then recovered shortly afterward. Within about 36 minutes a combination of high-frequency trading bots and the complex interplay of trading algorithms contributed to the rapid sell-off and rebound. Today this event is referred to as “the flash crash.”33

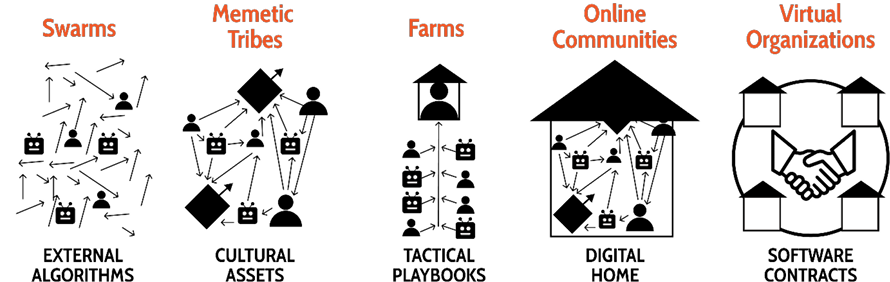

Online Formations

Swarms do not exist in isolation; instead they are part of a rich ecosystem of online formations. Through research, I identified four other archetypes of online formations: memetic tribes, communities, farms, and virtual organizations. Each archetype differs from swarms based on how they encode their own social protocols.

Swarms, as we’ve mentioned, are minimally protocolized; they do not have explicit protocols like a managerial hierarchy or central planning process. Instead, they rely on external algorithms for coordination.

Other archetypes encode explicit protocols into internal collaboration instruments such as cultural assets, tactical playbooks, gathering spaces, and contracts. Together, the family of online formations provides an overview of large-scale collectives in the virtual landscape.34

Memetic Tribes

The most infamous archetype today is arguably the memetic tribe, a term coined by Peter Limberg, an online culture researcher.35 This archetype is characterized by the creation and maintenance of cultural assets, often based on niche and dogmatic ideologies. Some examples may sound familiar: Black Lives Matter, MeToo, Occupy, QAnon, and Postrats. They are often confused with swarms due to their distributed nature, regular public feuds, and lack of a central gathering space.

Memetic tribes differ from swarms in various ways. Memetic tribes have known influencers and collective names. Peter Limberg in his “Meme to Vibe: A Philosophical Report”36 defines these tribes by their living philosophies which have a “distinct vibe, with a definite sense of ‘ingroup.’” To achieve this, a tribe develops its own cultural lore and assets.37 They might have custom meme templates and narratives, emojis-in-bio norms, and a plurality of user-generated manifestos.

Operationally, tribe participation is fluid and fragmented, relying on a daisy-chain network of influencers instead of managers.38 Like swarms, participants have a high level of agency; defining their own way of contributing. The glue, instead of a single promise, is their rich distributed repository of cultural assets. This provides the basis for a collective history and, consequently, a longer lifespan. A tribe known as Post-rationalists today, for example, can be traced back to 2009.39

Figure 5. Five archetypes of online formations, characterized by its primary collaboration instrument

Digital Farms

Like online swarms, digital farms are transient, don’t have a brand, and have shifting identities. Digital farms differ from swarms in having distinct playbooks for extracting value from networked ecosystems like games, social media, and the stock market.40

Gold farming,41 social influence farming, and crypto-airdrop farms42 are all different types of farms. In each case, participants are promised digital currency or the opportunity to receive it. These farms are characterized by the tactical nature of how they work and their reluctance to form a group identity that could be held accountable. Farms exist in dubious legal spaces, remaining viable only while the target arbitrage lasts.

Farms are quite common. For example, there are informal groups of people who follow each other on social media sites, and their playbook is simple: you follow me, I follow you, and we both look like we are influencers. These follow-farm members often have a tag like “follow-for-follow” in their profile bio and join group chats with hundreds of participants. More complex farms have dedicated Discord groups, Telegram channels, and newsletters with detailed playbooks. Searching for “buy follows” will surface dedicated ecommerce stores that sell farmed likes, followers, and views.

Online Communities

Online communities are similar to memetic tribes, but with a stronger presence of explicit social protocols. These communities include professional networks, fandoms, and hobby groups. Like tribes, they have cultural assets. Their distinguishing factor is a digital home:

a sense of locality that spans both the virtual and physical worlds of their users.43

This home can take the form of any central and recognized gathering space: website, knowledge hub, or social media neighborhood. It also can include a mind-space anchor, such as a celebrity, work of fiction, or brand. Across these spaces, communities apply codified rules of behavior, like community guidelines, enforced through moderation. The agreed gathering space also reflects the community’s strong sense of group identity and cohesive internal subgroups.

The most documented community subtype is likely fandoms.44 They are prolific contributors to online lore in the form of fan fiction, wikis, and public feuds. Examples of fandoms include Taylor Swift’s Swifties and the K-pop superfan group called the BTS Army. Fantasy world fandoms are also common, examples include communities like Potterheads, where fans of Harry Potter meet.

Unlike swarms, online communities work towards an internally consistent world: a home. They document their history in knowledge hubs, have known influencer networks, and reach a rough consensus on approved content. Potterheads, for example, create and gather content on specific websites about the Harry Potter universe and have extensive repositories of fan fiction.45

In advanced cases, communities have documented jargon, vision statements, and codes of conduct. Many fandoms also have channels of mobilization. Kaitlyn Tiffany, in her book Everything I Need I Get from You, explains why the British boy band One Direction holds the record for most Billboard awards in the top duo/group category: fans coordinated online for weeks to mass-purchase their music and stream their songs:

Instructions for supporting the project circulated on Tumblr and Twitter . . . fans planned to buy the song on iTunes as many times as possible . . . Everyone who participated was expected to keep [the song] on repeat on streaming services, request it on the radio, keep it trending . . . 46

Last but not least, communities differ from swarms because they curate their canon. Canon, such as official music and appearances, serves as an anchor; it is a source of digitally local truth.47 Unsurprisingly, communities adopt persistent identities, sometimes outlasting the celebrity’s life. The Beatles’ fans are still expanding their knowledge base and attending community-organized events, even though the band no longer exists.48

Virtual Organizations

A fourth archetype completes today’s online group landscape: virtual organizations. Blockchain organizations known as decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) are a key example. Virtual organizations can be considered a natural progression from online communities. DAOs also have cultural assets and knowledge hubs, but go further: they seek to enforce social protocols via code. They may have internal reputation scoring, budget distribution rules, and democratic governance models.

Gitcoin, for example, is a virtual organization that uses a novel concept called quadratic funding to distribute donations to public goods projects:

Individuals make public goods contributions to projects of value to them. The amount received by the project is (proportional to) the square of the sum of the square roots of contributions received.49

This social protocol governs the relationship between fund contributors and distributors. In a traditional organization, a user would “trust the product” to execute the organization’s stated process. At Gitcoin, little trust is necessary to process donations.50 The protocol is instead encoded directly into the code infrastructure. It is embedded into the organization’s built environment.

In many ways, internal infrastructure such as Gitcoin’s protocol allows virtual organizations to exist across platforms instead of within them. Had Gitcoin’s fund distribution ruleset been a process, instead of being encoded in a protocol, users and employees would have to trust the product suite that processed the funds. When we donate money through Facebook, we trust Facebook to process those payments fairly. Instead, Gitcoin has adopted an open, immutable, and decentralized protocol. This allows the public to verify the protocol, regardless of the platform they use to interact with it.

These benefits have their own costs. Launching and maintaining software-encoded social protocols can be expensive and risky. It requires teams of engineers to abstract coordination behaviors into modeled transactions and write secure code. The job is difficult: virtual organizations have been known to collapse under the weight of their own operations or get hacked. Encoding social protocols into software can be a double-edged sword, especially when digital currencies translate to “real” money. Dozens of DAOs have lost millions of dollars from their treasuries due to governance errors and malicious actors.51

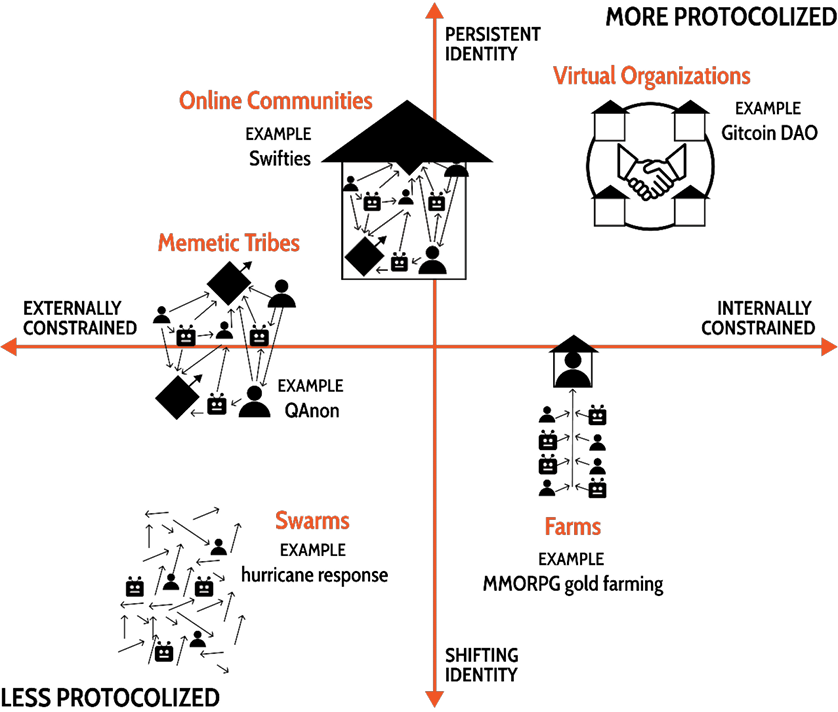

Protocolized Transformations

As we can see, each online formation manages its explicit protocols and encodes them into its infrastructure. This phenomenon isn’t restricted to online formations; even in traditional organizations like companies, established protocols like approval processes are in place to support their purpose, and, by definition, shape the broader cultural and operational structures. Whichever protocols are selected to fulfill the organization’s purpose will define its size and the relationships among its employees. Structure follows protocol.

Figure 6. Online formation archetypes can be roughly sorted based on their reliance on implicit and explicit social protocols. Swarms are minimally protocolized; they are reliant on implicit social protocols. In contrast, virtual organizations can have social protocols encoded into software.

We can look at the transformation from a swarm into a memetic tribe to illustrate this dynamic. Throughout their lifecycle, a faction in the swarm may adopt a set of preferred emojis and memes. These emojis, adopted universally by the faction, could then become associated with a name. Now the faction has its own cultural assets and banner. They have encoded a basic social protocol:

Use this emoji and name to broadcast your alignment with our values.

In other words, the faction has deployed an in-group management protocol. It is now a memetic tribe, with participants actively seeking out those using the emojis or who have the emoji in their social media bio.

The transformations arising from encoding explicit and uniform protocols have two primary consequences: identity persistence and collaboration constraints.

Swarms start off with shifting identities: no single name is accurate. This fluidity is associated with conflicting internal factions, rapid mutations, or simply a lack of language. In the Summer of Protocols program, as an example, the participants have been discussing possible options to name the field of study concerned with protocols. None have been agreed upon. This suggests that researchers studying protocols don’t belong to an online community or virtual organization yet. Instead, the network of researchers is likely a swarm, on the verge of becoming a memetic tribe: cultural assets such as these essays are being created.

In the case of Jorge and Pablo, both agreed on an indistinct, generic team name: Red de Apoyo Mutuo (Mutual Aid Network). However, this name was only for their close network of volunteers. As a swarm, there was no agreed name externally or internally. Jorge and Pablo’s team name was not adopted uniformly or used in news reporting to represent the broader swarm. It was, however, searchable and a quick way for their core team to broadcast their intentions.

In contrast, online formations with protocols embedded into their infrastructure, such as communities and virtual organizations, have identity persistence.52 As the label implies, they have an agreed name that is persistent across perspectives and over a significant time. WallStreetBets, as an example community, is named after their subreddit home. This name is the same for members, Wikipedia entries, and news articles. It has also been consistent since the infamous GameStop short squeeze in 2021.53 However, the name persistence does not imply a longer lifespan. Individuals, traditional firms, and nations may have short lifespans and names that persist in historical records.

Online formations that have a persistent, and agreed-upon name tend to have internal collaboration structures as well. These structures, collectively managed, constrain the collaboration to internal preferences. Virtual organizations, like DAOs such as Gitcoin, choose their contracts, operational processes, and approvals.

Less protocolized formations, such as swarms and memetic tribes, rely instead on informal peer-to-peer agreements. They are constrained by the external algorithms and protocols of the platforms they inhabit. Collaboration is guided by pattern recognition and platform features. Looking back at Jorge’s spreadsheet, anyone could make a copy without Jorge’s approval, as long as Facebook’s algorithms allowed them to discover it.

Alignment Technologies

Without constraining geography, a persistent name, or internal protocols to target, swarms are virtually impossible to communicate with or hold accountable. Like an insurgency, there is “no single person or small group in charge.”54 They require us to take on a new approach:

Our ability to summon, steer, and protect swarms will depend on how we can catalyze, shape, and preserve network structures and orientations.

Major social media platforms illustrate a first attempt at controlling swarms. They have deployed global content moderation programs and international Know-Your-Customer (KYC) protocols to address the risks of anonymity.55 They continuously combat harmful content by identifying and removing instigating posts, actors, and networks. Yet, the effectiveness of these tools remains limited56 and employing the tools can have severe mental-health consequences for moderators themselves.57 Herding shadows is no easy feat.

Moderation and KYC are examples of alignment technologies. Rather than telling participants how to act, allocating resources based on forecasts, or drawing out resources based on need, alignment technologies craft network structures and orientations.58 They are concerned with questions like: Who (and what) participates in this network? How should this network react? How is this network scaling? What is the network’s focus? In other words, they govern how networks like swarms can emerge, expand, morph, and dissipate.

At a tactical level, alignment technologies include features that introduce or remove network friction. For example, like, follow, shadowban, and block: affordances like these help participants garden their networks. At an operational level, tools exist that shift the communication context and discovery, including gated spaces like Facebook Groups and the discovery algorithm design. Should Facebook have decided to prevent the mutual-aid swarm, it would have likely dampened the reach of the swarm through tactical and operational tools. At a strategic level, alignment technologies include feedback loop design and worldbuilding, higher-level and longer-term designs. For example, defining the rewards of a networked ecosystem: which users get paid a share of advertiser revenue? how much? under what conditions?

Figure 7. Online formation archetypes plotted on a 2×2 grid based on identity persistence and collaboration constraints

Each of these alignment technologies influences network dynamics at different levels: content, agent, or as a whole. They also influence networks either reactively or proactively. In many ways, alignment technologies enable organizational jujitsu. They can serve as catalysts, build and redirect participatory momentum, transform adversarial spaces into cooperative ones, or dissipate malicious networks through disorientation.

Despite the ubiquity of examples, building and implementing alignment technology is still an emerging art. Basic features like mute and report are blunt tools used in social media ecosystems. Network participants are sculpting their relationships with hammers.

But companies continue to innovate. Moderation, for example, has become increasingly sophisticated. In 2018, Facebook introduced a Dangerous Organizations and Individuals policy setting out how Facebook will be managing networks, not just individual pieces of content:

Under this policy, we designate individuals, organizations, and networks of people.59

Challenges persist: how do you wrangle billions of people, content, and bots across hundreds of moving legal systems? And how do you do this while minimizing bias, supporting a plurality of beliefs and ethics, and addressing private interests?

A key consideration comes down to ecosystem intentions. Today, alignment technologies predominantly adjust networks and orientations toward a central entity’s objectives. Moderation tools ensure Facebook advertisements appear alongside brand-approved content, usually avoiding placement alongside unsuitable content. Reframing intentions might provide a new path: do alignment technologies need to rely solely on such assimilation? What might be possible if network attunement were supported instead?

Attunement Technologies

Attunement is the ability to become in sync. Originating in child development research, attunement has historically described a caregiver’s ability to tune into, recognize, and respond appropriately to a child’s needs and moods.60 Today it is also applied to interpersonal dynamics, like synchronized heart rates across people listening to the same story.61

Online, we can expand the concept to include tuning into and resonating with a collective narrative or crafting a shared direction. In general, we can use the term attunement to talk about mutual alignment, not alignment with a central actor. In stark contrast to tools like centralized content moderation, attunement technologies would promote shared understanding and cooperative action within a digital locality.

Figure 8. Alignment technologies can stimulate assimilation or attunement

A few examples of attunement technologies are emerging. One recent standard is X’s community notes feature:

Contributors can leave notes on any post and if enough contributors from different points of view rate that note as helpful, the note will be publicly shown on a post.62

In practice, this means that posts often display clarifying comments or are outright corrected by the users of the platform. Central moderation gives way to crowdsourced moderation.

Jokerace, a software program for credibly neutral surveys and contests, is another illustrative example.63 It hosts “races” where participants can submit proposals for a network to vote on. Similar to an open forum, Jokerace is a sensemaking space: networks can make decisions collectively. There is no central actor; instead, a course of action emerges from the network.

Individual communities are increasingly creating their own attunement software as well.64 An online community named Trust has developed an application called Bubble.65 This software automatically posts a message to Trust’s social media profile when that message has received a certain number of emoji reactions within the community. By doing so, Bubble allows the community to curate a public feed that reflects its collective preferences, and builds a shared narrative.

As we become more networked, opportunities for alignment and attunement technologies will become increasingly apparent. They present a possible path to support the success of swarms and other online formations while addressing platform business needs.

Summoned

For a long time, crowds, “unruly” physical testaments of public desire, have been the primary embodiment of collective action in the absence of explicit protocols. The momentum of crowds spurred unions and the civil rights movement and demanded peace in times of war. Crowds have also been used opportunistically as kindling for riots and mobs. These patterns are why we have “crowd control” protocols.

Today, we live and work within high-bandwidth networks alongside autonomous bots and content. And swarms have inherited the power and responsibilities of crowds.

As participants in swarms, we have already displayed an uncanny ability to deliver both constructive and destructive consequences. We can mobilize aid after catastrophic natural disasters, trigger international bank runs, create global games, and ruin careers. We can do this without explicit protocols, planning, or assigned leaders. The complex web of algorithms we inhabit is enough.

Private and public entities recognize this immense potential. Social media platforms play an active role in shaping, amplifying, and dissipating swarms. State actors summon swarms to support their political agenda. However, the current drive seems inward, profit-focused, and protective, a dangerous road focused on control: How can we restrain them? What value can we extract? What risk can we avoid?

Swarms, like crowds, can be symbiotic allies, not just resources or adversaries: What can we learn from swarms to address the global challenges we face today? How can we unleash their potential? Δ

————

Go to the ant, you sluggard!

Consider her ways and be wise,

which having no captain,

overseer, or ruler,

provides her supplies in the summer,

and gathers her food in the harvest.

—Proverbs 6:6–11

New King James Version

Author’s Note This research began as an inquiry on the nature of online swarms. While I initially sought to understand the protocols that characterized swarms, what I found was that the absence of protocols defined them. An online swarm as a minimally protocolized entity is a concept that weaves in core concepts from my fellow Summer of Protocols researchers Nadia Asparouhova in “Dangerous Protocols” and Kei Kreutler in “Artificial Memory and Orienting Infinity.” Both essays are recommended reading alongside this essay to better understand how protocols shape our world and how swarms relate to them.

Acknowledgments Thank you: Jorge and Pablo for your generous time and efforts in providing mutual aid to those in need, Renée and John for your deep practical expertise, Scott, Jihad, and Foster for the editing support, Sarah, Jay, Toby, and Kara for the imaginative discussions, Kei and Nadia for the pivotal insights of orientation and explicit protocols, Eric for the coaching, and the Summer of Protocols program for the opportunity.

Rafa Fernández explores and builds web3 collectives such as DAOs (crypto-native decentralized and autonomous organizations). Rafa is originally from Puerto Rico and now based in Berlin. Currently, he is supporting a large crypto-protocol with their decentralization efforts. In parallel, he is building Folklore, a self-funding, decentralised, and autonomous media network. rafael.fyi

-

1. The initial count of deaths acknowledged by the Federal Administration in 2017 was 65. In 2018, Governor Rosselló acknowledged the results of the George Washington University study which raised the estimate to 2,975 people. Another study, from Harvard University, estimated 4,645 deaths.

www.huffpost.com/entry/harvard-study-puerto-rico-death-toll_n_5b0d91d1e4b0568a880f2998

-

2. “According to the 2020 Decennial Census, there were about 3.29 million people living in Puerto Rico, a notable decline of 439,915 individuals from 2010 (–11.8%).” In Damayra I Figueroa-Lazu, Jennifer Hinojosa, and Yarimar Bonilla, “Puerto Rico’s 2020 Race/Ethnicity Decennial Analysis,” Centro’s Data Hub Coffee Hour, Center for Puerto Rican Studies, Hunter College, CUNY, 202. centropr.hunter.cuny.edu

“An estimated 5.8 million Hispanics of Puerto Rican origin lived in the United States in 2021, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.” In Mohamad Moslimani, Luis Noe-Bustamante, and Sono Shah, “Facts on Hispanics of Puerto Rican Origin in the United States, 2021,” Pew Research Center’s Hispanic Trends Project, August 16, 2023. www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/fact-sheet/us-hispanics-facts-on-puerto-rican-origin-latinos/

-

3. For this account I rely on conversations with both Jorge and Pablo.

-

4. The spreadsheet created by Jorge Vega Matos is still publicly available. docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1fyalhL8afPuAZ5gPbLI_oevEKGHXrJ7nYglMYY6O03s

-

5. In this essay I adopt Nadia Asparouhova’s definition of protocols outlined in her Summer of Protools essay “Dangerous Protocols” (2023). summerofprotocols.com/research/dangerous-protocols Protocols denote “procedural systems of social control that simplify communication between actors.” A detailed conversation on protocols is also in the Summer of Protocols pilot study, by Venkatesh Rao, Tim Beiko, Danny Ryan, Josh Stark, Trent Van Epps, Bastian Aue, “The Unreasonable Sufficiency of Protocols” (2023). summerofprotocols.com/research/module-two/the-unreasonable-sufficiency-of-protocols

-

6. Explicit protocols denote protocols which, as Nadia Asparouhva describes, “are clearly stated and enforced by physical constraints or a central authority.”

-

7. Byrne Hobert, “SVB: Of Balance Sheets, Brands, and Banks,” The Diff, March 9, 2023. www.thediff.co/archive/svb-of-balance-sheets-brands-and-banks/

-

8. It was very reminiscent of the scene from Mary Poppins: www.youtube.com/watch?v=xE5klz0yUT0

-

9. Wikipedia, “Collapse of Silicon Valley Bank.” en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Collapse_of_Silicon_Valley_Bank

-

10. For a detailed exploration of orientation, see Kei Kreutler’s essay, “Artificial Memory and Orienting Infinity.” Further discussion on orientation follows later in this essay. summerofprotocols.com/research/artificial-memory-and-orienting-infinity

-

11. Unlike traditional organizations, swarms rely on algorithms for coordination instead of uniform social protocols like planning processes, approvals, and chain-of-command.

-

12. Andrew Berdahl et al., “Emergent Sensing of Complex Environments by Mobile Animal Groups,” Science 339, no. 6119 (2013): 574–76. doi.org/10.1126/science.1225883

-

13. Chris R. Reid, Matthew J. Lutz, Scott Powell, Albert B. Kao, et al., “Army Ants Dynamically Adjust Living Bridges in Response to a Cost–Benefit Trade-Off,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, no. 49 (2015): 15113–18. doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1512241112

-

14. For a deeper understanding of crowds, I recommend Elias Canetti, Crowds and Power (New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1984).

-

15. Jorge and Pablo’s patterns of collaboration should not take us fully by surprise. Management theorists such as Simon Wardley highlighted the pattern over a decade ago. swardley.medium.com/how-organisations-are-changing-cf80f3e2300

-

16. John Robb, Brave New War: The Next Stage of Terrorism and the End of Globalization (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2007), p. 116.

-

17. Kreutler, 2023.

-

18. Another way I conceptualize the purest form of a swarm’s promise is to think of it as a passion (as defined by Hobbes) for a form (as defined by Plato). An infinite emotion for an unrealizable dream. This is one of the many reasons why it can be difficult to change the orientation of a swarm: it’s difficult to manipulate this type of collective vision.

-

19. “Yearn for the sea” is a call back to the beautiful phrase usually attributed to Antoine de Saint Exupéry, if not actually something he wrote: “If you wish to build a ship, do not divide the men into teams and send them to the forest to cut wood. Instead, teach them to long for the vast and endless sea.” en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Antoine_de_Saint_Exup%C3%A9ry

-

20. In the context of John Boyd’s OODA theory, orientation refers to the internal perspective an individual takes based on their observations and prior knowledge. See, for example, “Discourse on Winning and Losing,” lecturer, Col. John R. Boyd (ret.), USMC Command and Staff College, Marine Corps University, MCB Quantico, Virginia, 25 April / 2 May / 3 May, 1989. Transcript: static1.squarespace.com/static/5497331ae4b0148a6141bd47/t/5af842f8758d4615555d3f6d/1526219514965/Patterns+of+Conflict+Transcript.pdf

-

21. Peter M. Garber, Famous First Bubbles: The Fundamentals of Early Manias (Cambridge, Mass.: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2000), p. 81–81.

-

22. Dissipation may be the primary, but not the only possible “death” for a swarm. Further research should be conducted to understand when swarms transform, go dormant, or are permanently erased. For additional discussion on networked deaths, I would recommend Sarah Friend’s essay Good Death (2023), also part of the Summer of Protocols program. summerofprotocols.com/research/good-death

-

23. Jorge Vega Matos, “Ripples of Unconnectedness,” Thrive Global, November 4, 2018. community.thriveglobal.com/connection-in-the-time-of-almost-cholera/

-

24. Not only is it self-limiting, but hurricanes have an upper bound of intensity based on the ocean’s surface temperature. Kerry A. Emanuel, “The Maximum Intensity of Hurricanes,” Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 45, no. 7 (1988): 1143–55.

doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469

-

25. This set of six experiences of online swarms is non-exhaustive and not mutually exclusive. In many cases, swarms may present multiple styles at the same time. Furthermore, a swarm may be observed as different styles depending on the perspective of the observer. For example, a supportive activist may see a mutual aid mobilization while a critic may see an opportunistic frenzy.

-

26. Trends are also widely discussed as “hypes.”

-

27. Doubloons were named after the Spanish doblón or “double.”

-

28. Hello fellow traveler, please collect twelve doubloons to begin your journey.

-

29. The doubloon game followed all the characteristics of an online swarm. The game itself had no agreed name. Participants didn’t have a collective “we.” The coordination happened first on TikTok, then expanded rapidly across platforms including Facebook, Twitter, and Tumblr. Exposure to social media algorithms, which were pushing relevant memes for engagement, provided the backdrop for coordination.

-

30. Stephanie Kirchgaessner, Manisha Ganguly, David Pegg, Carole Cadwalladr and Jason Burke, “‘Revealed: the hacking and disinformation team meddling in elections,” The Guardian, February 14, 2023.

www.theguardian.com/world/2023/feb/15/revealed-disinformation-team-jorge-claim-meddling-elections-tal-hanan

-

31. Autonomous content includes media that is coupled to software contracts. This type of content is hosted on decentralized services such as the Ethereum blockchain and has its own predefined interaction rules.

-

32. Byung-Chul Han, In the Swarm: Digital Prospects (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2017), p. 56.

-

33. Wikipedia, “Flash crash.”

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flash_crash

-

34. Online formations included in the research exclude small-scale collectives such as trolling parties, teams, squads, cartels, duos, group-managed avatars, alts, and more. The research excluded conventional organizations, such as firms and states using online tools. For more about the impact of networks on social formations, I recommend danah boyd’s concept of the networked public discussed in her chapter, “Social Network Sites as Networked Publics: Affordances, Dynamics, and Implications,” in Networked Self: Identity, Community, and Culture on Social Network Sites (ed. Zizi Papacharissi) (United Kingdom: Routledge, 2011), pp. 39-58. www.danah.org/papers/2010/SNSasNetworkedPublics.pdf

-

35. A rich corpus of non-academic research exists regarding online formations. Examples include The Association of Internet Researchers, donotresearch.net, newmodels.io, and otherinter.net.

-

36. Peter N. Limberg, “Meme to Vibe: A Philosophical Report,” March 6, 2023. lessfoolish.substack.com/p/meme-to-vibe-a-philosophical-report

-

37. Cultural assets include uniform digital identifiers and memes such as hashtags, group names, digital homes, “big name” influencers, and ultimate aims (i.e., telos). Julia Rose DeCook reinforces this finding in her exploration of organizational structure and knowledge management practices for these groups in her dissertation “Curating The Future: The Sustainability Practices of Online Hate Groups” (Michigan State University, 2019).

doi.org/doi:10.25335/3c04-1e84

-

38. Influencers are digital avatars, managed by one or more people, that broadcast messages to a large following. They gain legitimacy by public favor. In contrast, managers are single individuals who provide direction, instruction, and context. Managers rely on hierarchy and credentials for legitimacy.

-

39. For example, Less Wrong, one of many rationalist blogs, was founded in 2009. forum.effectivealtruism.org/topics/lesswrong

-

40. Vili Lehdonvirta and Edward Castronova, Virtual Economies: Design and Analysis (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2014).

-

41. Gold farming emerged in the early 2000s in response to massive online role-playing games (MMORPGs) like World of Warcraft. Social influence farming includes actions by people who are paid to like, share, or reply to social media comments. Farming is also done without payment by fandoms in the hopes of manipulating social algorithms and increasing the visibility of the content of a target celebrity. Farming is prohibited by the terms of use or end-user agreements of all popular games and social media platforms. For more information, see Julian Dibbell, “Invisible Labor, Invisible Play: Online Gold Farming and the Boundary Between Jobs and Games,” Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment and Technology Law 18, no. 3 (2016): 419–465. scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw/vol18/iss3/2

-

42. Crypto airdrop farms include actions by people that aim to accumulate reputation points in the hopes of a future digital asset reward. For example, users may automate a high volume of transactions in new product to fake participation, trying to be rewarded with crypto-assets by the product company.

-

43. Elizabeth D. Mynatt, Vicki L. O’Day, Annette Adler, and Mizuko Ito, “Network Communities: Something Old, Something New, Something Borrowed . . .,” Computer Supported Cooperative Work 7 (1998): 123–56. doi.org/10.1023/a:1008688205872

-

44. As Henry Jenkins points out in Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture: “Its abbreviated form, ‘fan,’ first appeared in the late 19th century in journalistic accounts describing followers of professional sports teams (especially in baseball) at a time when the sport moved from a predominantly participant activity to a spectator event, but soon was expanded to incorporate any faithful ‘devotee’ of sports or commercial entertainment” (United States: Routledge, 1992, p. 12).

-

45. The website Fanfiction has over 90,000 entries under the Harry Potter category. Thousands of the fan creations are book-length entries. fanfiction.net

-

46. Kaitlyn Tiffany, Everything I Need I Get from You: How Fangirls Created the Internet as We Know It (United States: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022).

-

47. At times, disagreement on canon causes internal factions to develop. In the case of the band, One Direction, two factions appeared when fans disagreed on whether two members of the band were romantically involved with each other.

-

48. The website The Fest for Beatles Fans started in 1974 and still appears to be running. www.thefest.com

-

49. Vitalik Buterin, Zoë Hitzig, and E. Glen Weyl, “A Flexible Design for Funding Public Goods,” Management Science 65, no. 11 (2019): 5171–87.

doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2019.3337

-

50. Gitcoin, like many organizations, is targetted by sybils (nonhuman bots, often digital farming). As a result, Gitcoin launched a product called the Gitcoin Passport, which assigns privileges based on the likelihood that the account is a unique human. passport.gitcoin.co

-

51. Visit the website Rekt for an ongoing leaderboard of blockchain protocol hacks. rekt.news/leaderboard

-

52. Beyond a name, group identity also includes common beliefs, values, symbols, rituals, language, norms, etiquette, goals, and interests. In the case of online formations we will focus on name persistence and consistency across observer perspectives.

-

53. Wikipedia, “GameStop short squeeze.”

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/GameStop_short_squeeze

-

54. U.S. Army Field Manual No. 3-24 and Marine Corps Warfighting Publication No. 3-33.5, Insurgencies and Countering Insurgencies, chap. 4, paragraphs 6-7 (Washington, DC: U.S. Army and U.S. Marine Corps, 2014). irp.fas.org/doddir/army/fm3-24.pdf

-

55. Know-your-customer (KYC) is a standard process used in regulated industries like banking, financial services, and insurance to verify the identity of customers. The primary purpose of KYC is to ensure that customers are real people and are not involved in criminal activities like money laundering, terrorism financing, or identity theft.

-

56. Content moderation is underscored by Mike Masnick’s Impossibility Theorem: there is no perfect solution to content moderation. As Masnick highlighted painfully, “on Facebook alone . . . there are 350 million photos uploaded every single day . . . If there’s a 99.9% accuracy rate, it’s still going to make ‘mistakes’ on 350,000 images. Every. Single. Day” (emphasis in the original). “Masnick’s Impossibility Theorem: Content Moderation at Scale Is Impossible to Do Well,” Techdirt, November 20, 2019 (www.techdirt.com/2019/11/20/masnicks-impossibility-theorem-content-moderation-scale-is-impossible-to-do-well/). See also Joseph Bak-Coleman, Ian Kennedy, Morgan Wack, et al., “Combining Interventions to Reduce the Spread of Viral Misinformation,” Nature Human Behaviour 6, no. 10 (2022): 1372–80

(doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01388-6).

-

57. Casey Newton, “The Trauma Floor,” Verge, February 25, 2019. www.theverge.com/2019/2/25/18229714/cognizant-facebook-content-moderator-interviews-trauma-working-conditions-arizona

-

58. John Hagel presents a related concept called pull platforms. However, pull platforms “help to make resources and activities more accessible in flexible ways,” while alignment technologies strengthen network ties and strengthen its shared orientation. See John Hagel, John Seely Brown, and Lang Davison, The Power of Pull: How Small Moves, Smartly Made, Can Set Big Things in Motion (New York: Basic Books, 2010).

-

59. Facebook, “Dangerous Organizations and Individuals,” Transparency Center.

transparency.fb.com/policies/community-standards/dangerous-individuals-organizations

-

60. Jaclyn A. (Ludmer) Nofech-Mozes, Brittany Jamieson, Andrea Gonzalez, and Leslie Atkinson, “Mother-Infant Cortisol Attunement: Associations with Mother-Infant Attachment Disorganization,” Development and Psychopathology 32, no. 1 (2019): 43–55. doi.org/10.1017/s0954579418001396

-

61. Pauline Pérez, Jens Madsen, Leah Banellis, “Conscious Processing of Narrative Stimuli Synchronizes Heart Rate between Individuals,” Cell Reports 36, no. 11 (2021): 109692. doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109692

-

62. Twitter, “About Community Notes on Twitter.”

help.twitter.com/en/using-twitter/community-notes

-

63. See JokeRace for more on decentralized contests. jokerace.xyz

-

64. In some cases software is coupled to the online formation. In other words, it only works for the specific community or virtual organization. Called situated software, a term coined by Clay Shirky in an essay with the same name, the essay is archived here: gwern.net/doc/technology/2004-03-30-shirky-situatedsoftware.html

-

65. “Trust is a network of utopian conspirators, a sandbox for their creative, technical and critical projects, and a site of experimentation for new ways of learning together” (trust.support). “Bubble Voting is a community-driven protocol to foster and fund member projects. Interesting ideas bubble to the surface as members upvote each other’s posts in Discord. The representative and continuous voting mechanism is based on the success of Bubble Bot—the bot that allows Trust members to collectively push Discord posts to Twitter” (trust.support/feed/introducing-trust-fund-and-bubble-voting).

© 2023 Ethereum Foundation. All contributions are the property of their respective authors and are used by Ethereum Foundation under license. All contributions are licensed by their respective authors under CC BY-NC 4.0. After 2026-12-13, all contributions will be licensed by their respective authors under CC BY 4.0. Learn more at: summerofprotocols.com/ccplus-license-2023

Summer of Protocols :: summerofprotocols.com

ISBN-13: 978-1-962872-17-1 print

ISBN-13: 978-1-962872-43-0 epub

Printed in the United States of America

Printing history: May 2024

Inquiries :: hello@summerofprotocols.com

All illustrations created by the author.

Cover illustration by Midjourney :: prompt engineering by Josh Davis

«large, dynamic, and often chaotic group moving together made of small, closely packed dots or particles, exploded technical diagram»